Today I would like to talk a bit about horror fiction. It isn't brought up much on this blog because my knowledge on the subject isn't too vast, but I have been reading a bit about it recently and would like to share some observations. This is because horror, like just about everything else, isn't doing so hot these days. Though I suppose that isn't much of a surprise.

Horror used to be a force to be reckoned with back in the day. Even before it was a staple of the pulps it went back far into Gothic and Poe and into the classic fairy tales. But it was in the 20th century with its heavy reliance on visuals and the newly emerging cinema scene that it truly became a behemoth. When the horrors can be seen it tends to add a layer of realism to the proceedings. No wonder that it grew so large in such a relatively short time.

Throughout the '70s and '80s, and into the early '90s, the genre which had once been a staple of the Gothic flavored Weird Tales, and other such creepy places, had blown up thanks to the advent of books and movies such as The Exorcist, Rosemary's Baby, and The Omen. Evil was here, it is visceral, and it was going to get you! Considering the '70s were such a time of despair, it makes all too much sense that this sort of horror would appeal to the audiences. These movies helped show there was a sinister force in the dark hoping to make you miserable. It gave context for what made no sense on the outside. Anyone back then could relate to them and how they were filtered through the strange times around them.

I never grew up caring for horror. It might have been because the most popular form of horror when I was a kid was the slasher movie, which is a subgenre I still don't like all too much. Horror that focuses on gore is almost as bad as an adventure story that focuses on graphics sex: it's hardly the point of telling a story to begin with. I want to be unsettled at a world gone wrong that needs to be righted, not read long passages intimately describing torn flesh and broken bones before having an ending where everyone dies pointlessly.

That's all just gore and senseless violence. Horror is more than that.

What a good horror tale should do is a serve as a warning. The best of these stories focus on a character (hero or villain) breaking a taboo or rule and the consequences that spring from it. Everything is no longer as it should be because of this disturbance. The genre serves as a way to show what happens when what works and what is right is thrown away from that which doesn't, and results that spin out from that decision a character makes. It's about the importance of rules in a strong society, and how breaking them leads to destruction. All the best horror does this in at least some fashion, even if not obvious.

Horror needs heart. That is what gives it its power to shock and surprise.

As a result this makes it less of a genre and more of a theme. Horror can invade an adventure, it can appear in a mystery, and it can show itself in a romance. It can be any length from flash fiction to tome. It can come and go at the author's discretion. In other words, it is very flexible.

In fact, it was once tied together with what is called science fiction and fantasy in a mega-genre mashup where the author could emphasize any part of this behemoth they wished in order to tell their stories. The purest form of genre fiction bounces between elements of each to tell their tales of wonder. Not to mention there are the dark fantasies of fairy tales and myths from centuries upon centuries ago. But I've already gone over this before.

Fairy tales and legends also relied on rock solid morality. How can it not? It relies on the audience sharing an understanding of right and wrong that transcends what happens on the page or screen. Morality is what makes the difference between good and bad horror, and it is why so much of it no longer hits the mark. Author Misha Burnett once said the author's look on good and evil is what ends up changing the entire work. I agree with him.

He says:

"The main problem that I see with Stephen King in particular and modern horror in general is an inability to write a Good that deserves to conquer Evil.

"The modern horror protagonist is, at best, less bad than the monsters. In the more splatterpunk side of the genre, the protagonist is not even that–he’s just the one who ends up with the bigger gun at the end of the day.

"This is not to say that a horror hero must be a saint, but simply that the things for which the hero is fighting–the security of his home and family, the safety of the population in general, or even just his own life–should be acknowledged to be not just his own preferences, but objectively worthwhile.

"Moral relativism nerfs horror. If Joe is trying to stay alive and Blargdor is trying to kill him, the author should take a stand and say, “Joe is right to want to live and Blardor is wrong to want to kill him.”

"Instead, modern horror writers rely on increasingly gruesome depictions of violence and cruelty to try to awaken the reader’s sense of moral outrage.

"It is from that sense of moral outrage that the horror genre gets its power. A hurricane can kill people and destroy property on a great scale, but a hurricane is not a monster. (Granted, you can write a ripping yarn about people trapped in the path of a hurricane and struggling to survive, but it’s not horror.)

"To be monstrous, the antagonist must be not merely hazardous, but also wrong. Wrong in an objective sense–Something That Should Not Be.

"It is in the deliberate fostering of a sense of injustice that a writer invokes true horror.

"Killing a monster has to more than personal survival, it must be in itself a morally positive act.

"Injustice, however, requires an objective standard of justice to be measured against, and that is something that few modern horror writers are willing to portray."

This is why those stories of the 1970s broke out so big. It also had to do with the rising knowledge of satanic cults (believe it or not, they exist) and hangover from the tumultuous 1960s. People wanted to know what it was that was under the floorboards and hiding in their backyard. Who were the ones disturbing things and destroying the status quo? Why had things gotten so crazy?

These are questions horror can answer, and they can do it with imagination and wonder. You can fond solace in the unsettling.

Due to the success and rise of horror, pulp storytelling began to make a comeback in the 1970s. Much has been written about the sword and sorcery boom (horror is all over those) and even darker sf (the new wave was still on and had its own horror bent), but outside of the horror aficionados no one else really talks about horror's big boom. That might have to do with how little of it sticks with mainstream audiences these days, and hasn't for a while.

I know horror built itself a reputation as being about blood, guts, and dismemberment, something it was never really focused on before the 20th century, but that is only surface level. The best horror is about more than that. It must have been big if it lasted up until the early '90s (hmm) while fantasy and science fiction had died out sooner, and the classics fell out of print during this same period (more on this later). How did horror last so long?

'80s Horror is still looked back on as fondly as action movies from that time. Clearly there was a renaissance that stuck with audiences.

But then, like everything else, it flatlined in the '90s. Now horror is relegated to specialized indie publishers and random short story anthologies. You won't find much from Oldpub these days. They are all in on thrillers, and have been for over a quarter of a century. But for awhile horror was the cock of the walk.

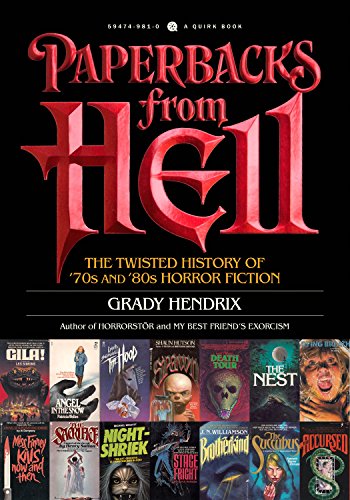

One book that went into this explosion was Paperbacks from Hell by author Grady Hendrix. This is a work covering that strange period of horror fiction between the '70s and the early '90s up to when Oldpub began to die and flushed out its classic genres and midlist. It's a highly engaging book, and well worth reading, if you can find it.

I personally read the kindle version. Either way you find it, it is worth the read.

|

| The book in question |

I have to say I was surprised with the scope of this book! The author does not skimp on details. Himself a fan of obscure paperbacks from the time period, Mr. Hendrix didn't really know much about them before beginning the book in question.

"The books I love were published during the horror paperback boom that started in the late ’60s, after Rosemary’s Baby hit the big time. Their reign of terror ended in the early ’90s, after the success of Silence of the Lambs convinced marketing departments to scrape the word horror off spines and glue on the word thriller instead. Like The Little People, these books had their flaws, but they offered such wonders. When’s the last time you read about Jewish monster brides, sex witches from the fourth dimension, flesh-eating moths, homicidal mimes, or golems stalking Long Island? Divorced from current trends in publishing, these out-of-print paperbacks feel like a breath of fresh air."

What Mr. Hendrix experienced is called "wonder", and it was a staple of the pulp-inspired fiction he was reading. It is about more than a mentally ill nihilist stabbing innocent people in back alleys and empty apartments. You don't get this sort of thing out of your common thriller.

You can see the same love of over-sized and large ideas from the pulps in his description, not unlike Jeffro Johnson writing about Appendix N in his own work. In today's stale Oldpub market of checkbox fiction, looking to the past is like being transported to a whole new dimension. It is a window into a world that literally does not exist anymore.

It is an intriguing development seeing so many people eager to look to the past to understand the decrepit state what they love is currently in. There has been quite the change over the last few years, and I don't suspect it will change any time soon.

Myself being one that grew up scrounging for anything good to read, it is always an annoyance reading these sorts of genre history books. If Mr. Johnson and Mr. Hendrix had been around when I was younger I might have been a much more voracious reader in my youth. I simply never found anything like these books when I was a boy which added a distaste for reading I never wanted. It is curious how many others were chased from reading due to these same issues.

But at least we can take these lessons forward now.

Being written before the politically correct '90s will do that. You simply aren't "allowed" to do that anymore. Even the worst fiction from that time is at least interesting due to avoiding needless rules that were tacked on by those who wished to control discourse and the flow of language by dismissing opponents with empty buzzwords instead of arguing or discussing anything. And because the work was so popular, editorial interference did not appear to affect it to the same level as, say, men's adventure. It was free to do what it wanted.

"The book you’re holding is a road map to the horror Narnia I found hidden in the darkest recesses of remote bookstores—a weird, wild, wonderful world that feels totally alien today, and not just because of the trainloads of killer clowns."

Being written before the politically correct '90s will do that. You simply aren't "allowed" to do that anymore. Even the worst fiction from that time is at least interesting due to avoiding needless rules that were tacked on by those who wished to control discourse and the flow of language by dismissing opponents with empty buzzwords instead of arguing or discussing anything. And because the work was so popular, editorial interference did not appear to affect it to the same level as, say, men's adventure. It was free to do what it wanted.

But now they all share the same shelves in used book stores. That is, if the shop carries them at all. And books outside of their designated shops? No chance of that. The drugstore paperback rack no longer exists.

"Though they may be consigned to dusty dollar boxes, these stories are timeless in the way that truly matters: they will not bore you. Thrown into the rough-and-tumble marketplace, the writers learned they had to earn every reader’s attention. And so they delivered books that move, hit hard, take risks, go for broke. It’s not just the covers that hook your eyeballs. It’s the writing, which respects no rules except one: always be interesting."

Welcome to the pulp revolution. This is what we want. I do not presume that Mr. Hendrix would want to be part of such a thing, but his excitement in discovering lost treasure is what started that very movement to begin with. We all wish to recover this strange energy lost to time in trying to please everyone and thereby ultimately satisfying no one.

We want it all, and we're going to make and take it!

However, while genre fiction was beginning to split into narrow categories and dwindling sales, horror remained rather locked in to where it needed to be. There was no John W. Campbell or his cronies trying to tamper and place rules on something that had none.

We want it all, and we're going to make and take it!

However, while genre fiction was beginning to split into narrow categories and dwindling sales, horror remained rather locked in to where it needed to be. There was no John W. Campbell or his cronies trying to tamper and place rules on something that had none.

Mr. Hendrix shares an interesting tidbit about 1960s horror:

"But if horror movies and television shows were stuck in the ’50s, horror publishing was trapped in the ’30s. While mainstream publishers were on fire with books like Truman Capote’s chilling true-crime shocker In Cold Blood, Jacqueline Susann’s titillating Valley of the Dolls, and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, the horror genre was taking its cues from the pulps of yesteryear. These books rarely even used the word horror on covers, instead offering “eerie adventure,” “chilling adventure,” “tales of the unexpected,” and “stories of the weird.” Even the work of Shirley Jackson, the empress of American horror fiction, was sold with covers that made her books look like gothic romances.

"It’s not that people weren’t buying books. After crashing in the 1950s, the paperback market surged back less than a decade later when college students turned Ballantine’s paperback editions of The Lord of the Rings into a zeitgeist-sized hit. Bantam Books reprinted pulp adventures of Doc Savage from the ’30s and ’40s, adding lush, photorealistic, fully painted covers by James Bama. And there was an early-’60s “Burroughs Boom” when publishers discovered that twenty-eight of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s books had fallen into the public domain. Suddenly, thirty-year-old Tarzan and John Carter of Mars novels were hitting stands, with new covers painted by Frank Frazetta and Richard Powers, alongside Conan reprints.

"Yet for all that activity, horror appeared nowhere on best-seller lists. Horror was for children. It was pulp. If it was any good, it couldn’t possibly be horror and so was rebranded as a “thrilling tale.” Horror seemed to have no future because it was trapped in the past. That was all about to change, and already there were signs that something was stirring. They were found in the romance section of the bookstore."

So you're telling me Weird Tales was still so popular even more than a decade after its shuttering? That is odd. I was told it had little to no effect on genre fiction by those writing genre fiction history books, if they felt it worth mentioning it at all. But this is quite an interesting nugget of information. Just as nothing was sold as "science fiction" or "fantasy", nothing was sold as "horror" either. It was all "adventure" and "weird" fiction.

Nonetheless, these books had Gothic covers because Gothic was an invaluable part of the horror experience for centuries, and it still is. The danger of the soul crossing invisible, but existing and real, boundaries is simply more in depth than simply being killed. This is the "weird" that makes weird fiction so very interesting. This is how Gothic romance stayed alive so long after Weird Menace quite nearly killed horror for good.

It is easy to forget, but as Ron Goulart mentioned in his History of the Pulps, Weird Menace was an embarrassment. It stripped the mystery and wonder of horror to focus on violence and debauchery instead. It didn't last. Much like Splatterpunk itself didn't, though that came along much later.

Nonetheless, these books had Gothic covers because Gothic was an invaluable part of the horror experience for centuries, and it still is. The danger of the soul crossing invisible, but existing and real, boundaries is simply more in depth than simply being killed. This is the "weird" that makes weird fiction so very interesting. This is how Gothic romance stayed alive so long after Weird Menace quite nearly killed horror for good.

It is easy to forget, but as Ron Goulart mentioned in his History of the Pulps, Weird Menace was an embarrassment. It stripped the mystery and wonder of horror to focus on violence and debauchery instead. It didn't last. Much like Splatterpunk itself didn't, though that came along much later.

Remember that the original Splatterpulps, Weird Menace, were such a flash in the pan and so hated that almost none of it was reprinted even now over half a century since the death of the pulps. Even horror aficionados have never gone on record wanting it back or begging for reprints. This is the sort of junk that kept horror held back as being looked at as "for kids" for a long time. Just as the pulps were looked at as kid stuff, even when a quick read of any would reveal that was not the case, horror suffered the same fate.

When scolds tell you what you like is amoral junk with nothing of value beneath the surface there is little point in setting about to prove them right. It never ends well, but it is simply a lesson we have to learn again and again.

When scolds tell you what you like is amoral junk with nothing of value beneath the surface there is little point in setting about to prove them right. It never ends well, but it is simply a lesson we have to learn again and again.

Still, the stigma stuck for decades.

With the death of the pulps in the 1950s, paperbacks had to be the ones to carry these wonder stories over into this new era. It only stands to reason that this form would continue well into the 1970s. Weird Menace was dead, but Gothic chills remained. How do you carry that to a new audience raised on an even steadier diet of visual media? You have to work on the image. This decade is when horror showed it could be a cultural force.

One last point on Gothic romance before I move on. I once said that the pulps tied together modern genre fiction with classic writings. Mr Hendrix agrees:

"Between 1960 and 1974, thousands of these covers appeared on paperback racks as gothic romances became the missing link between the gothic literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the paperback horror of the ’70s and ’80s."

Just remember the next time someone mentions the pulps were an aberration that needed its influence wiped out. They were anything but an anomaly.

This is a tradition that stretches back before the hopeless and empty modernism of today's fiction. The roots are deeper. It is far more classical focused, and obsessed with higher things. It all links together to form a much bigger picture.

This is where wonder comes from.

"Gothic romances seeded readers’ imaginations for the horror boom that was on the horizon. Brooding, shadowy mysteries were relocated to the domestic sphere, turning every home into a haunted castle and every potential bride into a potential victim. The blood of the resilient gothic heroine would flow in the veins of ’70s and ’80s heroines fighting to save their souls from Satan, or were-sharks. And were-sharks were coming. Because over on the other side of the bookrack, pulp fiction was getting interested in the occult."

The occult obsession in pop culture is not one dwelt on much, for obvious reasons. It's uncomfortable. But starting in the 1960s, interest in satanism (whether ironic or not, it really doesn't matter) grew to a fever pitch. Cult activity began to be a reality from Charles Manson and the strange happenings in Laurel Canyon up to the forming of the Church of Satan. The hippie movement's government ties and secret experiments provided fodder for stories from those just trying to figure out what was going on in this wacky decade.

There was more to it than the Beatles and what the television allowed you to see, and the public was starting to understand as much.

The 1970s carried this fear forward in an awkward way. Drug use and urban decay only exacerbated and the kooky cult activity began to be seeing eerie results from the Son of Sam and the Carr brothers that continued all the way up to the 1980s with the Chicago Ripper Crew and even the 1990s with The Kroth. There are more real stories than these including the Night Stalker Richard Ramirez and the seemingly random matriarchal murder by Jonathan Cantero. 27 members of the Order of the Solar Temple were found dead within hours of each other. There are many such examples that sprung from the 1960s to the current day. These were real things that were happening, no matter what the sex perverts with CIA ties who formed the False Memory Foundation told you. Things were happening that made no sense, and people wanted to make sense of it.

This rise in disturbing activity meant the populace needed answers. Where did all this evil come from? How do you make sense of it?

Enter horror.

This rise in disturbing activity meant the populace needed answers. Where did all this evil come from? How do you make sense of it?

Enter horror.

Horror is a good place to help make sense of it all. We can use the disturbances of the supernatural to allow us a lens to see this odd world around us. Things might be bad, but there are forces at work higher (and lower) than you understand. Somehow, despite the strange chaos, there is a point to it all. But are you brave enough to see it through?

This is what made horror so big. At least, it worked that way for awhile.

As society became more and more disheveled and broken down, horror became more interested in evil for evil's sake. Movies that exist solely for showing dumb people dying, books that go into graphic detail about cooked human flesh and over-descriptive blood drinking, and stories where the villain gets everything they want and wins in the end with no consequences became more and more common. That's not horror, that's just a bunch of things happening for no reason ending with nothing mattering at all. That is the opposite of giving purpose, and it is what lead to the genre's downfall.

Horror eventually succumbed to cultural rot just like everything else did. It was not for anything but the glory of death and the hatred of hope.

This is what made horror so big. At least, it worked that way for awhile.

As society became more and more disheveled and broken down, horror became more interested in evil for evil's sake. Movies that exist solely for showing dumb people dying, books that go into graphic detail about cooked human flesh and over-descriptive blood drinking, and stories where the villain gets everything they want and wins in the end with no consequences became more and more common. That's not horror, that's just a bunch of things happening for no reason ending with nothing mattering at all. That is the opposite of giving purpose, and it is what lead to the genre's downfall.

Horror eventually succumbed to cultural rot just like everything else did. It was not for anything but the glory of death and the hatred of hope.

By the '90s publishers switched over to thrillers because they no longer needed the supernatural. If you require mindless murdering and spilled guts then why do you need mythical monsters and ancient evils to perform it? Much easier to cut out the middleman and entice Hollywood studios to buy your book to make movies with lower budgets. You can also write an easier formula if you don't have to be creative in thinking up kooky monsters or events. Just stick it in the flaccid "real world" that the boring types love so much.

What do you need horror for anymore?

And there was no answer for this. If horror is just about mindless carnage then why can't the supernatural be stripped out of it? You can get just as much savagery with a crazed loon like Ted Bundy than a demon witch summoned from the fourth dimension to steal a hated sister's baby. If all you want is spilled blood then you don't need wonder any more. And they didn't.

What do you need horror for anymore?

And there was no answer for this. If horror is just about mindless carnage then why can't the supernatural be stripped out of it? You can get just as much savagery with a crazed loon like Ted Bundy than a demon witch summoned from the fourth dimension to steal a hated sister's baby. If all you want is spilled blood then you don't need wonder any more. And they didn't.

That this change happened so quick and so easily that no one noticed for decades afterwards should prove how off the rails horror had gotten so suddenly. I was as if they turned around and realized that the horror shelves were now barren. Where did it go?

What made the occult terrifying wasn't that it would murder you: it was that it sought to subvert and destroy normality by spinning everything backwards on on its head and infecting the innocent in its wake. In a climate where normality was slowly dying, no one could tell the difference between the good and the bad, and therefore horror lost its bearings. See how many modern horror stories are about "tortured outsiders" or horror nerds instead of normal people facing disturbing and outlandish events in their lives. "Normal" people are regularly spat on instead. It no longer became about appreciating the rules that kept the normal as it was, or about celebrating the common man, it became about hating normality and looking up to the disturbed instead.

The point of the Weird Tale had long since been forgotten, and in its place was a wacky, cartoonish inversion.

The point of the Weird Tale had long since been forgotten, and in its place was a wacky, cartoonish inversion.

Horror isn't supposed to hate people: it's supposed to love them. That is what makes conquering that which threatens them exciting. We want things to be set right again, and we want the horrible monster to fail. That is why horror loves rules so much: it wants people to follow them. If you don't? This is the mess you get in its place. You lose everything, and it's so much worse than merely losing your life.

This is partially why horror started from a religious POV. Higher things, rules, and clear defined stakes. Horror needs a structured playpen where it can then be free to play within its walls to its heart's content. Since it's about rules it only stands to reason that it needs them to function properly. Everything does.

When it lost the rules, everything else followed.

When it lost the rules, everything else followed.

As a result of this nonsensical change, by the '90s publishers had begun to dump aspiring authors, cutting off careers before they could even get off the ground and began pushing into thriller territory instead. They no longer needed horror, because horror had written its own self out of the picture. And nothing has changed on that end since the early '90s.

This change was exacerbated by the fact that the big boys in Oldpub bought up every independent throughout the 1980s. Per Mr. Hendrix's book:

When they decided horror was dead that meant it was dead. There was nothing you could do about it. The supernatural and the weird was "over", and now it was time for "realism" to shine. It has been "shining" since.

But there was more to it. A sledgehammer was taken to the industry that ended up irreparably harming books as a whole. The midlist, and potential industry growth in the process, was hobbled over night. The industry would never be the same again.

The Thor Power Tool Co. case is responsible for this change. Here is a description of the case from the book for those who might not be familiar with it.

Bye, bye, midlist. Now it was all about chasing the dragon of cheap cost for maximum profit in a short time frame. It was time to focus on being safe and finding hidden algorithms in public taste. Eventually that meant softening content to cast a wider net. Nothing is safer and more predictable than the thriller genre.

In case you haven't realized, Oldpub is still focused on thrillers to this day as their bread and butter. They have never shifted gears since. Nothing has changed in over 25 years.

And that is why we are where we are.

This change was exacerbated by the fact that the big boys in Oldpub bought up every independent throughout the 1980s. Per Mr. Hendrix's book:

"Small horror imprints had flourished in the ’70s, but in the ’80s the big publishers gobbled them up. Penguin acquired Grosset & Dunlap and Playboy Press, setting off a trend that snowballed into an extinction-level event by decade’s end. Once they had eaten the little guys, big publishers flooded the market with their own paperback original imprints, like Spectra, Onyx, Pinnacle, and Overlook."

When they decided horror was dead that meant it was dead. There was nothing you could do about it. The supernatural and the weird was "over", and now it was time for "realism" to shine. It has been "shining" since.

But there was more to it. A sledgehammer was taken to the industry that ended up irreparably harming books as a whole. The midlist, and potential industry growth in the process, was hobbled over night. The industry would never be the same again.

The Thor Power Tool Co. case is responsible for this change. Here is a description of the case from the book for those who might not be familiar with it.

"There was nothing the ’80s respected more than blockbuster success, and only brand names—V.C. Andrews, Anne Rice, Stephen King—would survive the decade. Blockbuster books permanently changed the publishing landscape, and it was all thanks to power tools.

"The Thor Power Tool Co. case of 1979 radically changed how books were sold. This U.S. Supreme Court decision upheld the Internal Revenue Service’s rule that companies could no longer “write down,” or lower the value of, unsold inventory. Previously, publishers pulped about 45 percent of their annual inventory, but that still left them with warehouses full of midlist novels that had steady but unspectacular sales. The pressure to sell quickly was off because publishers could list the value of the unsold inventory far below the books’ cover price. After the Thor decision, these books were valued at full cover price, eliminating the tax write-off. Suddenly, the day of the midlist novel was over. Paperbacks were given six weeks on the racks to find an audience, then it was off to the shredder. A successful book now had to sell blockbuster numbers. And manufacturing blockbusters took a team, starting with the blurb writer, who created the breathlessly enthusiastic marketing copy for the back cover. Then the marketing department came up with flashy gimmicks to help each book stand out in a crowded field. Publishers gave out porcelain roses, perfume, and garters bearing the names of their latest romances."

Bye, bye, midlist. Now it was all about chasing the dragon of cheap cost for maximum profit in a short time frame. It was time to focus on being safe and finding hidden algorithms in public taste. Eventually that meant softening content to cast a wider net. Nothing is safer and more predictable than the thriller genre.

In case you haven't realized, Oldpub is still focused on thrillers to this day as their bread and butter. They have never shifted gears since. Nothing has changed in over 25 years.

And that is why we are where we are.

This loss of identity is one horror readers have been lamenting for some time. Here is a recent video from In Praise of Shadows talking about this loss of identity in something that used to have a very obvious one. It's not a very long video, so please give it a watch before continuing. There are many good points he brings up.

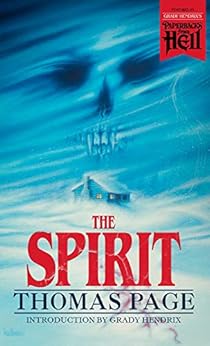

Apparently more authors and smaller publishers are noticing this dearth of content in the older horror vein. Newer authors have begun deliberately going back to the classic horror well. Companies like Valancourt Books have begun even offering special reprints of mass market paperbacks using Paperbacks from Hell as a brand.

This series takes old pulp horror novels from the above time period and reprints them using either the old covers, or covers not too dissimilar from what would be printed back then. As a result, they have created a classics line of obscure books highlighting exactly what the modern fiction world has been missing for some time. It's a mini-revolution.

This is a masterful move that gives focus to a neglected era of book publishing. Perhaps more readers can now see what they missed out on. The line is currently in its second wave with more to follow. There is some interesting material in there.

One such novel from this series is Nightblood by T. Chris Martindale, a writer who got his start on a choose your own adventure style series before getting the chance to write his own. This was an author with potential who worked his way up. He wanted to write the same sort of horror stories he and his brothers grew up on, and for his first big book pulled out all the stops.

The result s a story that would never see print today outside of Newpub:

|

| From the book |

Martindale's story of being an author is heartbreaking, as it is one of an author in the wrong place at the wrong time. He did his job, but that wouldn't be enough. He would never get the support he deserved to reach an audience he should have had.

Because Nightblood was published in 1990, he had a rough go of it and the same happened with the other three of his four standalone horror books. Horror was being faded out, even in 1990. He had a two book deal, including Nightblood, but never had the chance to write a sequel for it. His next novel was dumped on store shelves without promotion, and that was that. He was on his own.

Because Nightblood was published in 1990, he had a rough go of it and the same happened with the other three of his four standalone horror books. Horror was being faded out, even in 1990. He had a two book deal, including Nightblood, but never had the chance to write a sequel for it. His next novel was dumped on store shelves without promotion, and that was that. He was on his own.

Thankfully he had another two book deal with another publisher, but they were no better. The books were given bad covers and quietly released without any push in 1993 and '94. He was left floating in a stream without any paddle. He wrote the best books he could, but it was too late to matter. They decided horror was done. Publishers wouldn't do their jobs.

By 1994 no one wanted to do horror anymore, and he had nowhere left to go. He quit being an author and moved on to other things in frustration. What else could he do? There were no other options at the time if the publishers decided you weren't writing the correct books. So a promising career was cut short by editors and money men who decided to throw out the baby with the bathwater. The 20th century sure was the century of the editor above all else when it came to writing.

The men in charge decided that horror was out, so it was out. Who were you to disagree? The genre was dismantled almost overnight and those who like horror, and those who wanted to write it, simply didn't matter anymore. Stories of wonder, light against dark, and wild ideas of the supernatural, were out. Now it was about sterilized fear and rewrites of true crime fiction instead. Those wild and free ideas were finished.

The 1990s had decreed that imagination was outdated.

|

| The re-release looks just like the original |

Now even heavyweights such as Stephen King and Dean Koontz primarily write in the thriller vein and are given promotion as such. No one else will ever reach their level, no matter what they write. That door has been shut, locked, and the key thrown away. Whatever is left from when the genre was at peak popularity is all but gone from the old publishing world now.

Should there be a horror revolution, it's going to need to return to its roots and start from there. The age of Oldpub is over, and now it is the age of those with a PulpRev spirit: those who will break genre boundaries and bring back the focus and purpose that has been lost over the years. In other words, horror needs an attempt to move past the dead end state of fiction by returning to where it went wrong and taking a right turn instead. Lean into the wonder and the imagination. What else do you have to lose?

It's not about pretending the last however-many years didn't happen, it is about keeping that bad path in mind while forging ahead on better paths instead. This is how you move on: you learn from the past to move towards a better future.

Horror points to heaven, where the horrible and the unjust show where the good and the wondrous lie instead. It isn't meant to be about navel-gazing or mindless self-indulgence, but about connecting with readers and showing shared standards we can all believe in. Evil is evil, good is good, and one is definitely preferred over the other.

We're on the right track. The slow death of Oldpub and the explosive growth of Newpub shows just as much. Things are changing, and it's about time.

The '20s are going to be an interesting decade, and we're only just getting started! The revolution is here, and it isn't stopping anytime soon.

Yesterday I watched Raising Cain--a movie from 1992 I'd always meant to see but never got around to. It was directed by Brian de Palma and starred John Lithgow. I couldn't help but think of it as I read your post. Where Hitchcock would have made a horror film, Raising Cain uses every trick in the 90s book to turn the story into a thriller. What's most irritating is that the closest thing the movie has to a protagonist--Lithgow's strong, independent, adulterous wife--is less moral than the killer, but of course the movie decides halfway through that she should win all the marbles. It commits one of the two sins I can't forgive in a horror movie: The determination of who's the hero and who's the villain comes down to a coin toss.

ReplyDeleteThe other unpardonable sin is if the movie's ending is such that every character could have put a bullet in his head in act I without fundamentally changing the outcome. Looking at you, Frank Darabont.

I like my stories to have a point, and to respect me.

DeleteAbout the time horror became obsessed with gore for the sake of gore was when I discovered it. As a consequence it took me a very long time to take it seriously.

You tell stories to connect with people. Showing them a world where nothing matters and nothing you do will make a difference so just lay down and die is not one that offers anything to anyone. There's no connection being made, just a lot of meaningless sound and fury.

Horror at its best is about meaning since it's about rules. Horror that discards that discards the whole point of it existing.