For the fourth part of our series we touch on two of the biggest tropes in science fiction and fantasy, and we deal with what brought them about. Of course because we are being guided by Mr. Lundwall we have to be reminded at just what a great and marvelous time we are (were) living in.

The 20th century was a hot mess of good intentions and brazen attempts to seize the new throne in the expanding wild west of civilization. Whereas it started with wars, sparks of ideas, and hope, it ended in wars, decadence, and pure nihilism. In every respect that counted it was an utter failure. Much of this change came from the shift of existential thinking twisting to focus on the broken, meaningless, and endless, quest for man to finally take his place as master of the universe. Many lives had to be sacrificed for this goal that never happened, and never will, but it wasn't for lack of trying.

Fiction itself changed from being a past-time to entertain the masses and instill satisfaction and optimism as they went about their day building civilization, to being about ways to teach and instruct them their place under the boot of ideas from big brained men that were clearly superior to them. The people were taught to hate themselves, their ideals and their beliefs, and, of course, their past. They were made to look back with scorn towards a world run by fools that was nothing like the magical wonderland of emptiness they live in now.

Science fiction was a particularly useless tool in this endeavor ending in what is known as the science fiction ghetto where friends give each other awards and everyone who has the incorrect view is *miraculously* a terrible writer and is therefore justified in not being rewarded or talked about. One look at the embarrassment known as the Hugo Awards, and how few people pay attention and how small sales are gained from the nominations and winning, would be enough to tell you that much.

So it's when I find a book like Science Fiction: An Illustrated History that I feel a sense of relief. It is not just my paranoia speaking, but proof that the group of Fandom's elite have had a stranglehold on a fractured and small segment of fiction and squeezed the life out of it so hard that the pulp, juice, and even the orange peels, have been ground up into atoms leaving no trace behind. Whatever we had at the beginning of the 20th century was lost by the end, and it was done deliberately.

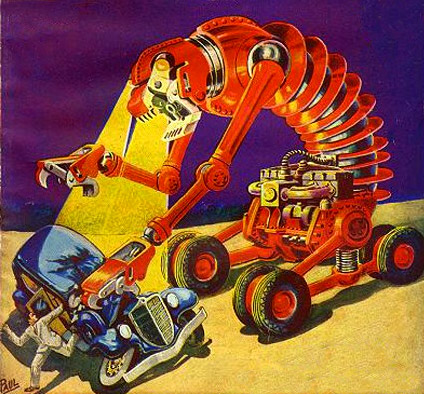

For example, the next chapter in Mr. Lundwall's book is about one of the 20th century's favorite subjects for fiction: robots. How can they change the way we operate in the modern world and what changes could they bring about? The answers are not as plentiful as you might think, especially from our current position in the neighboring century.

But of course we have to go back to the beginning first. Very early in the chapter Mr. Lundwall takes on a topic that current heads of Fandom are apparently too lazy to look into themselves as this particular bit of science had been settled mere decades ago. That would be the constant and ever-shifting usage of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein as a weapon to politicize science fiction with endless arguments about how badly women are treated in a genre that has never treated them badly. To do this we must blow up a Gothic Horror story to cartoonish proportions in order to exaggerate the influence that it actually had.

The fact of the matter is that Shelley created nothing: she was part of a tradition bigger than herself.

"Some critics think Frankenstein was the first science fiction tale ever written. It was obviously not, but this traditional British Gothic tale with the German Marchen tales proved successful and popular . . . "You see, the arguments over this always shift. The current masters of Fandom cannot be consistent for even one second.

First it was "the genres never mixed" . . . until it is brought up and shown conclusively that they did. Then it was true that X genre didn't start until Y story . . . when that is easily proven false by the words of those they deem the originators. Then it is changing the usage of words like "genre" in order to get the meaning they want out of the word.

It never ends.

The only reason this happens is so that a small clique can continue playing pretend in their sandbox away from the big dumb mean kids who used to beat them up every day after class in high school. It is personal validation. It is a way to put themselves above others by deifying the raygun romance books they read, all while using terminology and examples from usurpers who can't even keep the story straight mere decades later. The worst selling genre has no claim to elite status: it has a claim to basement and fire sales and being a laughing stalk to anyone watching from the sidelines.

There is a certain level of arrogance about being seen as above the common sheep for diving headfirst into propaganda, not being self-aware enough to realize you have been swallowed by it, then chastising those not spreading the propaganda in lieu of giving the audience what they want. But it wouldn't be Fandom otherwise.

Case in point:

"The robot clanked on in North America, getting more silly and murderous with every passing day, and it probably would have stayed within the realms of the penny dreadfuls had it not been for two now classic works, one novel and one play, that saved this ingenious tool for social commentary from the American pulp jungle (or, rather, saved the robot in Europe. Nothing really happened in the United States until the late 1940s)."If it wasn't for those blasted pulps giving the audience what they wanted: entertainment instead of a sermon!

Truly if we're being serious, robots have a very limited shelf-life in what they are capable of in stories. There is the everlasting quest for a soul, and there is the man-made monster that turns against its creator. sometimes both in the same story. The audience enjoys both which is why they have stuck around for so long. But as stated in the Monsters section the audience has a particular fascination with the weird and the dangerous. So enemies are the more popular usage of robots.

Not to mention there has been a trend for anti-human authors to use robots to stand in for the oppressed and man to stand in as whatever enemy they have in their heads at the time. This particular approach has never truly stuck with audiences for the same reason that most terrible genre fiction doesn't. The audience doesn't want to be told how worthless they are by people who hate them.

I'm going to be straight, and this will not be a popular view, but I will say it anyway.

The reason audiences and writers of the time were more interested in reading and writing fun stories that expanded wonder and imagination instead of trying to preach messages and change society is because they already had a religion. They already went to church, gave to the poor, ran for political offices, had communities they trusted, ran social programs, and believed in something higher than they were, which gave them a purpose. They didn't need what the elite were peddling.

The audiences weren't pathetic enough to need a story about a robot with the personality of a dish rag or mopey oppressed aliens to give their lives' meaning. They already thought about these things through theology, non-fiction, philosophy, and discussions. They read raygun romances for other reasons: it was to imagine that world of wonder and excitement that they already knew existed. They didn't need stories to paint the numbers in for them.

This is why the most successful stories of the 20th Century are entertainment based works that present a world where the heroic is rewarded and the dastardly is denounced. Audiences are already smart enough to have their own worldviews, they don't need to get them from silly books that will be found for a nickel at garage sales or left in a landfill.

But still this attitude from Fandom persists that they need to create their own religion to fill the void that can't be taken by talking these issues out or reading a non-fiction work or going to church. Still this idea persists that a low selling subgenre is worthy of being the modern bible of secular thinking. Still the Mediocre Word must be preached.

One look at today's climate is enough to show that it is the wrong approach, and the one audiences want less than anything. What they want is to soar the skies: not be chained by ideology.

With that I'm going to move on to the next chapter. The rest of this one is typical of Mr. Lundwall and will just be treading water should I follow on. Instead, I want to continue from my last point about escapism into the next chapter. This shows the split in difference between the clique and the normal reading audience.

For a case in point of how the existence of Fandom hurts others, see the attempted burying of the subject of the next chapter: Galactic Patrol. This might objectively be the worst chapter in the entire book. That is right, the author wrote an entire chapter based on the only popular version of science fiction: the space opera, and thrashed it.

Of course, as established, the space opera is pure adventure and escapism. There is nothing the customer loves more, so naturally Fandom abhors it. Now, let us see how the audience is wrong.

He begins the chapter using E.E. Doc Smith's Lensman series for creating his definitions:

"... [T]he fundamental fact of any self-respecting space opera tale is that the hero is, literally, the greatest, bravest, most handsome and most intelligent man in the entire universe, a wonder of a man who can out-think and out-draw any being in this universe or the next. He is ruthless when the need arises, but he is always willing to risk his life for blue-eyed and fair-haired WASP females in distress."Not much in the way of being charitable, is it?

I'm not quite sure what the skin color or beliefs of the women have to do with anything unless the author is trying to imply something sinister about Smith or his work. Not to mention that alien (and therefore, foreign) women are a main attraction of most of Edgar Rice Burroughs' tales. But Burroughs has been quite ignored this entire book aside from an offhand mention or two.

It's about keeping the message on target, not being truthful. Already this chapter is off to a horrendous start via a generalization and attempted tarring of a giant of the genre. That he has to do this should set off alarms for any honest reader.

For now we will let this slide. What is more important is this next part where he describes a passage in the final E. E. Smith Skylark book and compares it to a western.

One might consider this respectful and somewhat accurate. Many action tales have their roots in the warrior archetype, and the cowboy is one that the west is infamous for. It is a fair comparison and once again establishes a link with a long-running tradition. Warriors are men at their peak: brave, strong, and a force to be reckoned with.

What kind of fiction would be poor and miserable enough to defecate on such a person?

Before Fandom took control? Propagandists. I am not exaggerating. But at this point it is to be expected. Demoralization is important to create change, and it is a very useful tool to create social change. Destroying the western is paramount to this.

Mr. Lundwall doesn't let us down. He does his comparison between the space opera and western like this:

"However, E. E. Smith assures us, "No human world was destroyed." This shows that the hero is a nice guy after all, although forced by circumstances to out-do all the mass murderers in history. Whereas the Wild West, or Horse Opera, hero defends the white race and Western civilization with his trusty six-shooters, the space opera hero carries the White Man's Burden on his broad shoulders around the entire universe, killing off everything that appears too alien. The difference lies not in attitude or philosophy, but in scale; at bottom, we still have the age-old desire to externalize evil, to create adversaries that are truly and unquestionably evil. It is too easy to feel compassion for Indians, Chinese or Vietnamese--thorough evil, as embodied in Satan or the Alien, comes closer to the mark. Thus, the space opera tale vindicated a bloodlust that is all too common in this day and age."There is so much to unpack in this one passage I hardly know where to begin. Nonetheless this is all buzzwords and mantras taken from a classroom with no weight in reality.

Needless to say, he is wrong.

I could explain the nature of evil and why readers enjoy this sort of story once again, but that would be repeating myself. It's easy to say that people enjoy stories where the hero is good and someone to aspire to and where the villains are the exact opposite. That would be true. It's simple dynamics. I'm certain the author would unquestionably assert Adolf Hitler is a pure black hat that deserves no pity. And yet he asserts such people do not exist with idiocy like his above passage. This is a typical trick of moral relativists to assert insane things they do not really believe in order to cover for some vice they do not wish to disclose. But that is hardly the audience's fault.

Whether black and white hats exist or not is irrelevant. This is a story where they do. This is how imagination works, as poisonous as it is for Fandom to admit. To assert that readers (and writers, by extension) read this material because they believe those who think differently than themselves are total demons and wish to see them eradicated is an intellectually childish and outright insane conclusion to jump to.

The author might need to actually talk to someone who reads these stories. A lot of these assumptions are nutty and pure lunacy to an outsider looking in. But since he did the same to Christian beliefs in an earlier chapter I would say understanding his fellow man is not at the top of his list when it comes to being a science fiction scholar. Not when there is subversion and table-tipping to be done.

Now as for charges of genocide and the author's obsessive and frothing hatred of White Anglo Saxon Protestants I can only say it borders on dementia at this point. It is also completely off-topic, though admittedly not off-message. By this point we know which is the more important of the two.

No one who has read a western thinks they are about crushing the Natives and enforcing their values on them because they aren't about that. At all. This is revisionism to try and paint those who lived back in another time (and another continent, as our author is not from North America) as horrible irredeemable monsters who should have their evil influence wiped out. This is fiction, according to Mr. Lundwall, that exists to grind its heel in other peoples and cultures.

At the time of that writing I'm fairly certain he had never read a western. The only people who say these sorts of things about the genre have never engaged in it or deceptively pick outliers to prove their vapid points.

Westerns are about good, normal people living in a lawless land trying to find peace and order while the bad threaten to overwhelm and destroy what has been built. This is battle between extremes on a knife's edge. It's once again a black and white situation which the author hates because his imagination towards such situations is limited. But no, it's an evil racist genre with no good to it at all. Whether he truly believes that or not is hardly the point. He needs the audience to believe it so he can get it out of the way.

The irony of this hatred coming from someone who reportedly doesn't believe in straight black and white morality is blindingly ridiculous. Every time the author uses the term "WASP" it is a code-word for "bad" or "evil" and nothing else. This is ridiculously transparent.

But lastly, the passage is infuriating because it is implying that E. E. Smith is a white supremacist. Why else would he write such works? Mr. Lundwall has already said several times that if an author writes it he believes it, so this is his charge. As stupid and obviously wrong as it is it must be stated anyway. There is a genre to destroy here.

Mr. Lundwall makes his assertion based on nothing but a shallow interpretation of a genre he has never bothered to understand beyond what his overlords in Fandom told him to believe about it. In the process he has painted Smith as either a racist, an idiot that didn't know what he was writing, or cashing in on his audience's internalized hatred of the other. No matter how that is read it is an insult and uncalled for.

The chapter has just begun and it is already off the rails.

He then goes on to explain George Griffith's novel Stories of Other Worlds (1900), which is what he considers the first space opera.

It does indeed share much of familiar aspects of the genre from world hopping to martian threats to larger than life heroes and villains. For a moment we are almost back on track again.

Of course the author can't help himself making stupid claims, and this one is a humdinger.

"Here, then, is the mould in which all space opera stories have been cast. Details are different in modern space opera, but the basic attitude is the same. This is apparently what has made this particular branch of science fiction so popular and, in my personal opinion, rather dangerous. Racism and the glorification of violence is still the main ingredient of space opera, albeit usually discreetly hidden somewhere among the mind-boggling space armadas."Everything is sexist, everything is racist, and you have to point it all out all the time, indeed. This is tin-foil hat territory.

This is the problem with having an ideology as a religion. You see things in other people that they themselves don't see as if you are some sort of psychoanalyst or mind reader. You're not. You do not know them better than they know themselves. You are not a Special Person or Secret King. Especially not in this case where the author does not even know what a western actually is yet feels confident explaining them.

People enjoy things because the aesthetics tickle their fancy on a surface level and the themes resonate on a deeper level. The themes that resonate with audiences are natural and normal. The ones that are carefully concocted in cluttered classrooms by those who use a failed economist's guidebook as their bible are not natural. They are made to subvert, misrepresent, and destroy, so that they may take the place of the original and the agent can be hailed as a genius.

And what else is Fandom's goal but to control?

Starting to see what happened to science fiction? Unless you believe writers and readers of space opera and westerns are simply racist because of a nebulous form of indoctrination that can't be quantified except by those who themselves get their beliefs from admitted subversives and propagandists, that is. Then you might see nothing wrong. But that is a level of insanity that can only be taught.

It amazes that such blatant cultism was allowed in the front door and nobody said anything.

Of course what would be a space opera chapter without the requisite jabs at the audience's intelligence?

"In essence, they were written for boys by a writer that never quite grew up; E. E. Smith is like a child playing with stars and galaxies, without bothering for a second about credibility or morals or anything that could possibly take the fun out of the game."For a man like Smith who was widely read by scientists and engineers (like Burroughs was) this is a profoundly stupid statement. Few writers in the 20th century inspired audiences to the level he did, never mind raygun writers. And he did it with tales of wonder, excitement, and celebrating the good. Our author has completely missed the point. But what can one expect of someone whose idea of "growing up" is believing exactly the same anti-social drivel as he does.

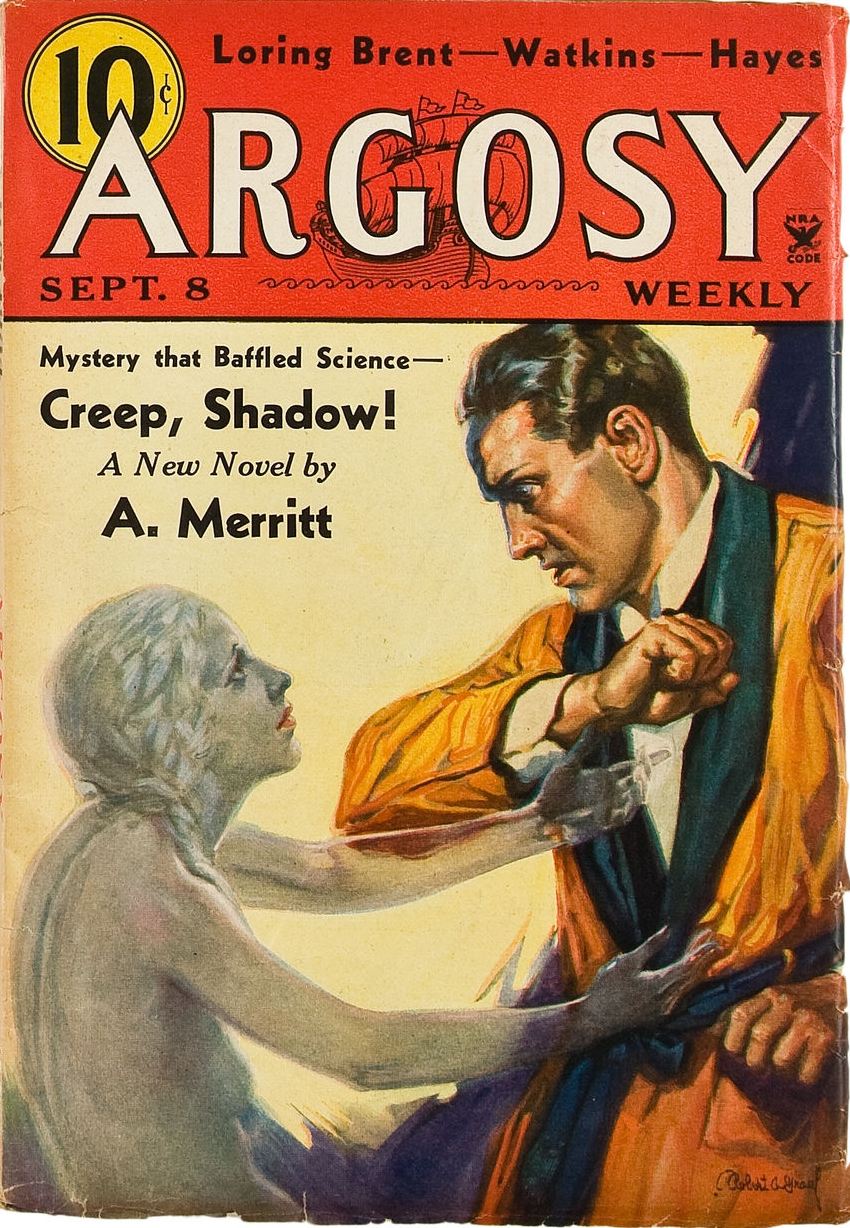

I have heard tell that E. E. Smith was respected when he was alive, but I have never seen such a dishonest attempt to smear the dead since Damon Knight's offhanded insult of Abraham Merritt's appearance. There is no sense of tradition or respect for those that came before in this industry. How can there be when there is a constant game of thrones going on behind the scenes that no one except Fandom gives two spits about.

Respect for the dead isn't on the author's radar, and neither is it for the, at the time, recently deceased. This is what Mr. Lundwall had to say about Edmund Hamilton who died just as this very book was coming out in 1977:

"Edmund Hamilton (1904-1977) was a surprisingly mature and sensitive author who might have become one of science fiction's most important writers had he not spent most of his time and energy writing blood-and-thunder juvenile space operas is, however, most fondly remembered for one series of space opera novels, rivalling E. E. Smith's novels in popularity."If only he would have spent his time writing what the clique wanted they might not have tried to keep his works out of print and hard to find over the years. Marvelous. Also, a classy passage to have in this book the very year Hamilton died. He is one of the most important writers of the genre despite this blatant attempt at revisionism before the body has even gone cold. These agents work fast.

Fandom's quest to tinker with the past is a never ending game.

Hamilton is fondly remembered as one of the best writers of genre fiction for those who had ever bothered to read him and was highly influential in the field, even if he didn't write the "correct" books. He was a man who wrote works where genre boundaries didn't matter much and the universe was as wide open with possibilities as his stories were. He was one of the titans of the field, and pretending otherwise is deceit. That he isn't currently in print is a crime.

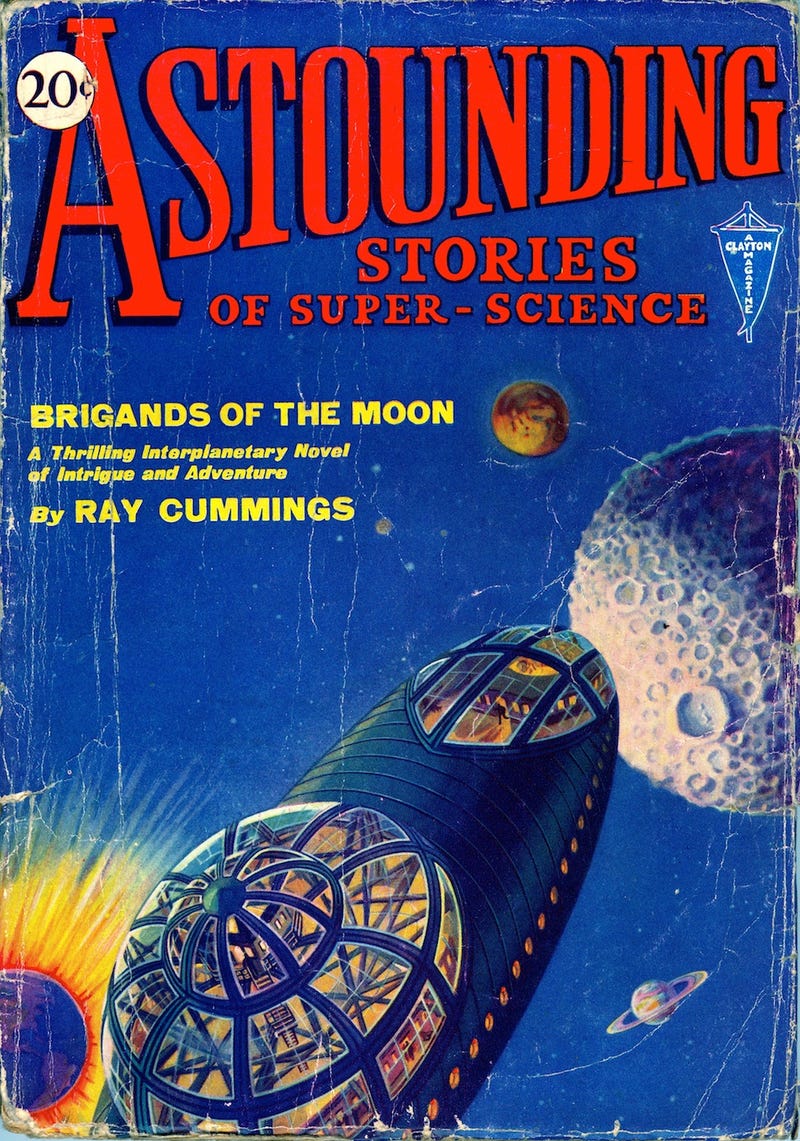

According to the author, Hamilton's only real competition for the space opera crown was John W. Campbell.

"For some years in the early 1930s Hamilton was competing for the place of the leading American space opera author with John W. Campbell (1910-1971) who produced quite a number of incredible space opera yarns . . . until in October 1937 when he found his true vocation as editor of Astounding Stories (Now Analog), and started an editorial career during which he advocated the ideas of a large number of cranks, notably former science fiction author, now prophet, L. Ron Hubbard, whose strange religion Dianetics, now Scientology, found its first home in Astounding. Campbell wanted to create super-science in real-life; Hamilton was more modest."It isn't that well known today that Campbell was an author since not long after taking control of Astounding Stories he spent most his time subverting the original intent of the magazine and by 1940 shaking out all the older mainstays in the magazine. But one of these two gets lauded, and the other gets tossed off as a curiosity.

As a side-note, it was Campbell's predecessor F. Orlin Tremaine who picked up and ran E. E. Smith's Galactic Patrol, H.P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness and Shadow Out of Time, and Colossus by Donald Wandrei, among many others in Astounding's pages. Tremaine also wrote stories and contributed to such magazines as Weird Tales and even wrote detective stories. He was also involved in Christian, humor, and many different types of magazines from Crime to Romance throughout his editing career. He did much. It is a fascinating career.

I bring this up because Tremaine has been airbrushed out of most genre discussions as if he was utterly disposable to Fandom. Perhaps he was. He edited and wrote to appeal to a mass market audience and genre boundaries didn't appear to matter all that much judging by what he was willing to publish. He was not interested in turning stories into secular scripture and yet he was responsible for much of what others take credit for. He helped make Astounding Stories a success.

Mr. Lundwall does not mention F. Orlin Tremaine once during this entire book that is meant to cover the genre's history. His name is not even brought up in an offhand manner. This is worth mentioning. That tells us quite a bit about the aims of this work.

Especially when unneeded and rude passages such as this drivel are included:

"A whole generation of American fans who read these stories during their formative years still think Captain Future is the greatest literature ever written."Or this:

"It also appears that Perry Rhodan fans read very little science fiction except the Perry Rhodan stuff--naturally enough, since Walter Ernstring et al have managed to cram all hack science fiction into this single series."No citation needed, of course. The smear is more important than the job of a scholar. Fandom approves.

But perhaps the best insult is saved for last. This is a case of missing the forest for the trees so hard that one ends up walking into a lake instead:

"For space opera is, when you get down to it, not a matter of futurism or credibility or literary quality or any of the traits that makes good science fiction good; it is Sense of Wonder in pure undiluted form, the dreams of the absolute, unlimited power as the basis, and gigantism and good versus evil as the main ingredients. It takes place in space and the far future, since this gives ample room for gigantism, but apart from that it has more in common with Wild West fiction than modern science fiction. It is not good literature by any standards, and it is certainly not good science fiction . . . it has always been written by hacks who cared little about what they wrote, as long as they got paid for it."It is also the only version of science fiction that sells to this day despite Fandom burying the works and keeping them out of print and out of focus except to insult and smear the long deceased writers. There is nothing Fandom hates more than escapism because they cannot use it as a social engineering tool. Reminder that this book released in 1977 just before Star Wars came out to prove this assertion that Fandom hates Wonder. How many tortured explanations of "Star Wars is not science fiction" have you heard? You can safely ignore them all. They were spearheaded by subversives who specialize in destroying the past.

This lie needs to be pointed out, and this revisionism needs to end. Fandom must be called out for the destruction they have enacted. Do not peddle lies by those who hate you.

Space opera is about grand scale happenings in an unlimited world and space where possibilities are endless. It goes beyond the small cracked mirror of the moderns and instead takes place in a frame where the edges are quite nearly invisible and the future is ongoing. Anything can happen in a world where wonder rules and hope reigns supreme, where man can rise beyond themselves to face problems beyond their own petty ones. It is an ode to joy in prose form.

Yes, space opera is more than hack literary fiction with nuts and bolts sprinkled in the cracks by authors begging at the table of New York cocktail party elites: it's about the wide-open future and far-off worlds beyond our own that anyone can reach. One is tiny and warped and the other is big and bright. As God has decreed: the universe is endless! Anything can happen, and everything does. How is that for excitement and wonder?

It is only a shame that Fandom is filled with those who would rather navel gaze about their genitals or petty personal problems they can't talk out with their loved ones instead. They have chosen a small-minded sandbox to play in when they could have whole planets, suns, and galaxies. It is a self-hating thing for a writer to scorn imagination.

Is it any wonder how things got as bad as they are now?

That is all for this part. Next time we reach our final installment! The author once more journeys into the Pulp Jungle and asks the human question, and we will be there with him. There will be more to discuss.

Thank you once again to everyone sharing this series. It has been a strange trip, and it is only getting stranger. We're almost there. One more to go!