This has been a long road we've gone down on the journey through Fandom's past. One can clearly see just how much of their culture was created by outsiders attempting to create a clean sweep of the world for their own purposes. They are not your friends; they are not anyone's friends. All they wish to do is spread their cult into the wider world, and will use anything and anyone as a weapon to get there. This where the fabrication of "Science Fiction & Fantasy" came from. Before their arrival, they were all romantic adventures, fairy tales, and gothic horror.

But we've already been over all that. There is more to it than what was taken away. Today we shall talk about what has been preserved.

I do not want to keep harping on the Fandom subject forever, so I wanted to cap off the series with this supplemental edition. Today we will end on the history of what might be the most important magazine of the pulp era, if not objectively in the top 3. Since it has been scarcely covered in the series so far (you'll see why soon enough) I found it best to finish on a positive note by going in deep on something Fandom has been trying their best to downplay and/or subvert for nearly a century. Today we will be talking about Weird Tales (1923-1954), the Unique Magazine.

As a consequence, this episode is going to be far different than the last few. We are going to see the difference between Fanatics and Normal People. I say this, because those involved with Weird Tales could hardly be any different than the weirdos we've talked about so far. Yes, even with their idiosyncrasies, the folks who made Weird Tales what it was were relatively healthy people, or people trying to be. There are no cultists here.

I wanted to cover Weird Tales because despite the history of the pulps, the revisionism they've been soaking in for nearly a century, the Fandom cult constructing a parallel mythology around their preferred reality, and the general malaise oozing from the industry, Weird Tales is a magazine that was an anomaly in a lot of ways, even for a market as strange as the pulps. We are going to discover just how true that is today.

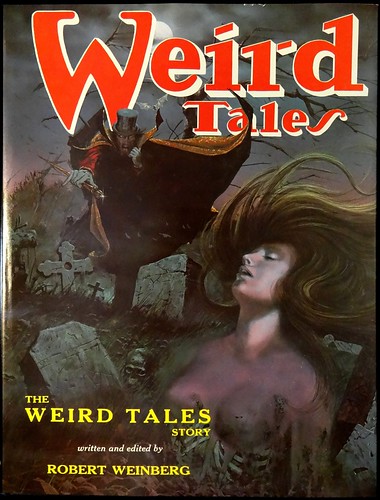

Today we are going to look at The Weird Tales Story by Robert Weinberg from 1977 (reprinted in 1999). This is one of the very few books on the history of the magazine (and one of the few on any of the pulps) when even Ron Goulart's otherwise great book we covered earlier completely skimmed over it. This is the final piece of the puzzle in our series, and we're going to cover it today.

I'm reading from the recently released expanded edition released in 2022, which contains articles from many other modern writers and scholars with experience in this arena including an introduction by author Adrian Cole. From all I can find it looks as if Weinberg's original text remains the same across all editions, so there will be little difference in what we go over.

As for the additional material in the book, there are plenty of visual examples of covers and interior art. The fresh pieces by the new writers mostly center upon short biographies of important authors published in Weird Tales, as well as a chapter written by Morgan Holmes on sword and sorcery in the magazine and how it moved towards sword and planet. There is also an end piece on what happened to the Weird Tales brand name since the original magazine ended for good in 1954. I highly recommend reading all of that material as it is very good information supplied on a history in danger of being forgotten. Given that this is one of the most important magazines of the 20th century (Black Mask and Argosy being just as important) it should be discussed far more than it has been--especially by supposed scholars of the "field" they supposedly love so much.

Without further ado, let us go into the history of Weird Tales. For that we have to go back a very long time into the past.

It should be added that this book is important as it is one of the few written while the writers and artists were still around to talk about it. Mr. Weinberg admits he has favorites (Howard, Lovecraft, and Hamilton, chief of them) yet allows the writers and artists to do their own speaking for themselves. In other words, this work is straight from the horse's mouth.

As an example:

"This book was made possible through the assistance of many people. Foremost among them was Leo Margulies, without whose aid this work could never have been written. Each contributor who shared his memories helped make this work a bit more complete. E. Hoffman Price and Margaret Brundage, both of whom answered innumerable questions about their association with Weird Tales as well as the actual magazine itself, have to be singled out for their invaluable assistance.

"Many others contributed important information. They included Glenn Lord, Celia La Spina, Vincent Napoli, Tom Cockcroft, Sam Moskowitz, and J. Grant Thiessen."

You might recognize some of those names. That someone was smart enough to interview them while they were still alive is rather important for a history. This also means that there won't be another work that can do what this one does.

"The most famous writer of weird fiction in the English language was the literary grandfather of Weird Tales. J.C. Henneberger, the creator and thus father of the fantasy magazine, explained Edgar Allan Poe's importance in the following:"

Keep in mind that this was written in the 1970s when Fandom terms had finally been forced on the rest of us. You will see a lot of terms never used when Weird Tales was actually being published being used throughout this book. At this point revisionism had already taken hold. It does not change the core story, however. That said, let us get back to Mr. Henneberger's quote.

"As a lad of of 16, I attended a military academy in Virginia. The English department was headed by one Captain Stevens, a hunchback who was a rather chauvinistic chap in that he favored Southern writers. One entire semester was devoted to Poe! You can imagine how immersed I became in him!"

Mr. Henneberger's youth was then spent trying to create new avenues and places where the stories he enjoyed could flourish and prosper. It was rather difficult then, especially since the pulp magazine was such a new thing, but eventually he reached his goal. And how grateful we are that he did! It took a lot to keep the magazine running for over 30 years.

In 1922 he started up Rural Publications with J.M. Lansinger, and immediately got to work on two magazines. The first was a detective magazine, the second was Weird Tales. The latter was the passion project, one that he refused to abandon.

As he says:

"Before the advent of Weird Tales, I had talked with such nationally known writers as Hamlin Garland, Emerson Hough, and Ben Hecht then residing in Chicago. I discovered that all of them expressed a desire to submit for publication a story of the unconventional type but hesitated to do so for fear of rejection. Pressed for details they acknowledged that such a delving into the realms of fantasy, the bizarre, and the outré could possibly be frowned upon by publishers of the conventional...."When everything is properly weighed, I must confess that the main motive in establishing Weird Tales was to give the writer free rein to express his innermost feelings in a manner befitting great literature."

Though this probably a bit embellished, it is true that such a weird magazine had little chance of succeeding unless they really dressed to impress. There hadn't been much like it aside from the ill-fated Thrill Book which came out some years earlier and died within a handful of issues. They essentially had to build a market for themselves.

To succeed, he enlisted the services of Edwin Baird, a well known writer in Chicago. Baird, in turn, had two people help him. They were Farnsworth Wright, a music critic, and prolific writer and author Otis Adelbert Kline.

Mr. Baird was an "idea man" as the book describes, and once the magazine got off the ground, he lost inspiration in editing it. This shows in the early days of Weird Tales not really establishing much of an identity outside of ghost and monster stories and the occasional curveball. Despite this, it wasn't a complete washout.

Mr. Baird was only there for around a year, leaving in 1924. Due to reorganizing and selling off his other magazines, he left with the detective magazine and Mr. Henneberger put Farnsworth Wright on as the new editor. Mr. Wright would then stay with Weird Tales for 16 years, from 1924 to 1940. This would be the move that would save the magazine.

Farnsworth Wright is written about a lot in this book, and for good reason. He is much of the reason for Weird Tales' success and his editing skill is practically unmatched. He's also quite a character, as we'll soon see.

"Farnsworth Wright (1888-1940) was born in California. He was educated at the University of Nevada and the University of Washington. When the United States entered World War I, he went to France as a private in the infantry. He served as a French interpreter in the American Expeditionary Forces for a year. In 1919, Wright had a mild case of sleeping sickness. Two years later, it returned in the form of Parkinson's disease. The condition worsened throughout the rest of Wright's life. By the end of the 1920s, the shaking caused by the disease was so bad that Wright could not sign his name."

That's right, throughout his entire tenure at Weird Tales, Mr. Wright had a disease that only worsened and ate at him further. Despite that, he never stopped doing what he did to the best of his ability. Even though it would eventually take his life, he fought it for nearly two decades. That is something to be said about a man who frequently dealt with the fantastical on a daily basis.

Mr. Wright married in 1929 and had a son a year later. In 1940 he left Weird Tales due to his health, even having an operation to try to help with the growing pain. But it did not help much, and he died in June of that year. He had quite the life, but we will get to that.

First let us see what he was like as an editor.

"Wright was a canny editor. Rarely did a good story get past him, even from an unknown author. Weird Tales featured more stories from authors who were only published with one tale than any other science fiction or fantasy magazine. Wright got stories from everywhere and everyone. [...] Wright once stated that of 100 manuscripts submitted, approximately two were bought."

There is one thing you might have noticed from everything written here so far, and it is a very important thing to note. Have you grasped it? It is quite amazing, especially considering everything we went through with the rest of the Fandom series.

The entire motivation behind everyone involved in Weird Tales was purely for monetary and artistic reasons--not social engineering. There was no materialist cultism at play here. There is no sinister motive behind Weird Tales, nothing evil or antisocial. It was purely about creating a unique magazine for an audience to buy: to offer something truly fresh. That is it, and it is reflected with everyone written about so far, including the undeservingly ignored Otis Adelbert Kline who played a large part in the success of the magazine, and gets little credit for it.

Mr. Kline also wrote this piece for the magazine nearly 100 years ago entitled "Why Weird Tales?" which was only revealed to be him many years after the fact. The entire thing is free online in the original magazine print. This piece is fairly illuminating.

It says:

"Up to the day the first issue of WEIRD TALES was placed on the stands, stories of the sort you read between these covers each month were taboo in the publishing world. Each magazine had its fixed policy. Some catered to mixed classes of readers, most specialized on certain types of stories, but all agreed in excluding the genuinely weird stories. The greatest weird story and one of the greatest short stories ever written, “The Murders of [sic] the Rue Morgue,” would not have stood the ghost of a show in any modern editorial office previous to the launching of WEIRD TALES. Had Edgar Allan Poe produced that masterpiece in this generation he would have searched in vain for a publisher before the advent of this magazine.

"And so every issue of this magazine fulfills its mission, printing the kind of stories you like to read—stories which you have no opportunity of reading in other periodicals because of their orthodox editorial policies.

"We make no pretension of publishing, or even trying to publish a magazine that will please everybody. What we have done, and will continue to do, is to gather around us an ever-increasing body of readers who appreciate the weird, the bizarre, the unusual—who recognize true art in fiction.

"The writing of the common run of stories today has, unfortunately for American literature, taken on the character of an exact science. Such stories are entirely mechanical, conforming to fixed rules. A good analogy might be found in the music of the electric piano. It is technically perfect, mechanically true, but lacking in expression. As is the case with any art when mechanics are permitted to dominate, the soul of the story is crushed—suffocated beneath a weight of technique. True art—the expression of the soul—is lacking.

"The types of stories we have published, and will continue to publish may be placed under two classifications. The first of these is the story of psychic phenomena or the occult story. These stories are written from three viewpoints: The viewpoint of the spiritualist who believes that such phenomena are produced by spirits of the departed, the scientist, who believes they are either the result of fraud, or may be explained by known, little known, or perhaps unknown phases of natural law, and the neutral investigator, who simply records the facts, lets them speak for themselves, and bolds no brief for either side.

"The second classification might be termed “Highly Imaginative Stories.” These are stories of advancement in the sciences and the arts to which the generation of the writer who creates them has not attained. All writers of such stories are prophets, and in the years to come, many of their prophecies will come true.

"There are a few people who sniff at such stories. They delude themselves with the statement that they are too practical to read such stuff. We cannot, nor do we aim to please such readers. A man for whom this generation has found no equal in his particular field of investigation, none other than the illustrious Huxley, wrote a suitable answer for them long ago. He said: “Those who refuse to go beyond fact rarely get as far as fact.”

"Writers of highly imaginative fiction have, in times past, drawn back the veil of centuries, allowing their readers to look at the wonders of the present. True, these visions were often distorted, as by a mirror with a curved surface, but just as truly were they actual reflections of the present. It is the mission of WEIRD TALES to find present day writers who have this faculty, that our readers may glimpse the future—may be vouchsafed visions of the wonders that are to come.

"Looking back over the vast sea of literature that has been produced since man began to record his thoughts, we find two types predominating—two types that have lived up to the present and will live on into the future: The weird story and the highly imaginative story. The greatest writers of history have been at their best when producing such stories; Homer, Shakespeare, Milton, Dante, Irving, Hawthorne, Poe, Verne, Dickens, Maeterlinck, Doyle, Wells, and scores of other lesser lights. Their weird and highly imaginative stories will live forever.

"Shakespeare gave forceful expression to the creed of writers of the weird and highly imaginative, when he wrote the oft-quoted saying: “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

"The writer of the highly imaginative story intuitively knows of the existence of these things, and endeavors to search them out. He has an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. He is at once, the scientist, the philosopher, and the poet. He evolves fancies from known facts, and new and startling facts are in turn evolved from the fancies. For him, in truth, as for no others less gifted “Stone walls do not a prison make.” His ship of imagination will carry him the four thousand miles to the center of the earth, “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the, Sea,” on a journey to another planet millions of miles distant, or on a trip through the Universe, measured only in millions of light years, with equal facility. Material obstacles cannot stay his progress. He laughs at those two bogies which have plagued mankind from lime immemorial, time and space. Things without beginning and without end, which man is vainly trying to measure. Things that have neither length, breadth nor thickness, yet to which men would ascribe definite limits.

"To the imaginative writer, the upper reaches of the ether, the outer limits of the galactic ring, the great void that gaps beyond, and the infinity of Universes that may, for all we know, lie still further on, are as accessible as his own garden. He flies to them in the ship of his imagination in less time than it takes a bee to flit from one flower to another on the same spike of a delphinium.

"Some of the stories now being published in WEIRD TALES will live forever. Men, in the progressive ages to come, will wonder how it was possible that writers of the crude and uncivilized age known as the twentieth century could have had foreknowledge of the things that will have, by that time, come to pass. They will marvel, as they marvel even now, at the writings of Poe and Verne.

"It has always been the human desire to experience new emotions and sensations without actual danger. A tale of horror is told for its own sake, and becomes an end in itself. It is appreciated most by those who are secure from peril.

"Using the term in a wide sense, horror stories probably began with the magnificent story of the Writing on the Wall at Belshazzar’s Feast. Following this were the Book of Job, the legends of the Deluge and the Tower of Babel, and Saul’s Visit to the Woman of Endor. Byron once said the latter was the best ghost story ever written.

"The ancient Hebrews used the element of fear in their writings to spur their heroes to superhuman power or to instill a moral truth. The sun stands still in the heavens that Joshua may prevail over his enemies.

"The beginning of the English novel during the the middle of the eighteenth century brought to light Fielding, Smollett, Sterne and several others. Since this time terror has never ceased to be used as a motive in fiction. This period marked the end of the Gothic Romance whose primary appeal was to women readers. Situations fraught with terror are frequent in Jane Eyre. The Brontes, however, never used the supernatural element to increase tension. Theirs are the terrors of actual life. Wilkie Collins wove elaborate plots of hair-raising events. Bram Stoker, Richard Marsh and Sax Rohmer do likewise. Conan Doyle realized that darkness and loneliness place us at the mercy of terror and he worked artfully on our fear of the unknown. The works of Rider Haggard combine strangeness, wonder, mystery and horror, as do those of Verne, Hitchens, Blackwood, Conrad, and others.

"Charles Brockden Brown was the first American novelist to introduce supernatural occurrences and then trace them to natural causes. Like Mrs. Radcliffe, he was at the mercy of a conscience which forbade him to introduce spectres which he himself did not believe. Brown was deeply interested in morbid psychology and he took delight in tracing the working of the brain ip times of emotional distress. His best works are Edgar Huntly, Wieland and Ormond.

"The group of “Strange Stories by a Nervous Gentleman” in Tales of a Traveler, prove that Washington Irving was well versed in ghostly lore. He was wont to summon ghosts and spirits at will but could not refrain from receiving them in a jocose, irreverent mood. However, in the Story of the German Student he strikes a note of real horror.

"Hawthorne was not a man of morose and gloomy temper. An irresistible impulse drove him toward the sombre and gloomy. In his Notebook he says: “I used to think that I could imagine all the passions, all the feelings and states of the heart and mind, but how little did I know! Indeed, we are but shadows, we are not endowed with real life, but all that seems most real about us is but the thinnest shadow of a dream—till the heart be touched.”

"The weird story of The Hollow of the Three Hills, the gloomy legend of Ethan Brand and the ghostly White Old Maid are typical of Hawthorne’s mastery of the bizarre. His introduction of witches into The Scarlet Letter, and of mesmerism into The Blithedale Romance show that he was preoccupied with the terrors of magic and of the invisible world.

"Hawthorne was concerned with mournful reflections, not frightful events. The mystery of death, not its terror, fascinated him. He never startled you with physical horror save possibly in The House of the Seven Gables. In the chapter, Judge Jaffery Pyncheon, Hawthorne, with grim and bitter irony, mocks and taunts the dead body of the judge until the ghostly pageantry of the dead Pyncheons—including at last Judge Jaffery himself with the fatal crimson stain on his neckcloth—fades away with the coming of daylight.

"Edgar Allan Poe was penetrating the trackless regions of terror while Hawthorne was toying with spectral forms and “dark ideas.” Where Hawthorne would have shrunk back, repelled and disgusted, Poe, wildly exhilarated by the anticipation of a new and excruciating thrill, forced his way onward. Both Poe and Hawthorne were fascinated by the thought of death. The hemlock and cypress overshadowed Poe night and day and he describes death accompanied by its direst physical and mental agonies. Hawthorne wrote with finished perfection, unerringly choosing the right word; Poe experimented with language, painfully acquiring a studied form of expression which was remarkably effective at times. In his Masque of the Red Death we are forcibly impressed with the skilful arrangement of words, the alternation of long and short sentences, the use of repetition, and the deliberate choice of epithets.

"But enough of Poe. His works are immortal and stand today as the most widely read of any American author. The publishers of WEIRD TALES hope they will be instrumental in discovering or uncovering some American writer who will leave to posterity what Poe and Hawthorne have bequeathed to the present generation. Perhaps in the last year we have been instrumental in furnishing an outlet to writers whose works would not find a ready market in the usual channels.

"The reception accorded us has been cordial and we feel that we will survive. We dislike to predict the future of the horror story. We believe its powers are not yet exhausted. The advance of science proves this. It will lead us into unexplored labyrinths of terror and the human desire to experience new emotions will always be with us.

"Dr. Frank Crane says: “What I write is my tombstone.” And again—“As for me, let my bones and flesh be burned, and the ashes dropped in the moving waters, and if my name shall live at all, let it be found among Books, the only garden of forget-me-nots, the only human device for perpetuating this personality.”

"So WEIRD TALES has, from its inception, and will in the future, endeavor to find and publish those stories that will make their writers immortal. It will play its humble but necessary part in perpetuating those personalities that are worthy to be crowned as immortals.

You can read more from the transcriber, Terence E. Hanley, here on his site. He writes extensively about Weird Tales and others from that era. Definitely check his work out for yourself. He has uncovered a lot of good information.

Once more, it is a shame that Mr. Kline's work is not available in better condition or distribution. He certainly deserves the attention so many others from era command. Despite being a writer and also heavily involved in publishing, he had no Fanatic tendencies about him. He simply loved creating that much.

As for Farnsworth Wright, he was also fairly far from being a Fanatic. In fact, he was quite the interesting character. Mr. Weinberg talks about how he met with Mr. Wright and Mr. Kline and the two of them would go dining and even call themselves the "Varnished Vultures" as they would joke around eating dinner together. He did not have much in the way of pretention about him or his job, and that is rather different from the rest of the Fanatics.

He even helped a fledgling writer named Robert S. Carr get his career off the ground--a writer that was not a Weird writer or even submitting to Weird Tales at all. Eventually Carr got a Hollywood contract for his work and became friends with many involved in Weird Tales.

"An editor, they say, is a would-be writer whose frustration is expressed by grinning fiendishly as he stuffs a rejection slip into a return envelope. That's the most popular tradition, and like most widespread theories, it's way off the beam, simply because a man so warped by resentment could not maintain the open mind needed for his duties. But if that thesis were only partially justified, Farnsworth would have been an outstanding exception. In helping Bob Carr make his first step from what was, and still is, a magazine of limited circulation, he was depriving himself of a contributor who had been a drawing card from the start. [...] He was even ill and overworked, for in addition to his editorial duties, he was a music critic for a Chicago paper."

As far as the world of writing goes, Mr. Wright was fairly Chestertonian about it. This does not feel like a man full of himself.

"Our opening definition of an editor may have been an unfair implication: to wit, that Farnsworth nobly avoided the effects of frustration. This is not the case. I read one of his published slick paper stories, done years before he took charge of Weird Tales. There were others, though I remember only that one, which, incidentally, he did not give me time to finish. He showed it to me for only one reason: the yarn contained a pun in French, and he was proud of that! And he dismissed his writing by saying that he soon realized that while he could sell fiction, he could not produce sufficient quantities to make a living."

While it would have been interesting to see what a man like Mr. Wright would have done as a pulp writer, he definitely knew talent when he saw it. He always chose the story over the name author, which is why he even rejected stories by Lovecraft, Smith, and Howard, while they were alive and in their prime (and they made it known how they hated him for it!). He was always looking for the tale before the writer.

This is how he avoided cliques, and instead acquired a stable of writers that were the best of the best, because they had to be in order to get in. There is a very big difference between how he worked and how the rest of the industry soon became. They wanted their friends in; he wanted the best work in to satiate the audience.

Mr. Wright loved words, loved puns, and just loved the craft of writing as a whole. This is what allowed him to be the editor that he was.

"I repeat, Farnsworth loved words: the relish with which he would recite George Sterling's "Wine of Wizardry" is the most certain clue to his lavish appreciation of my first novelette. Prose, to him, needed rhythm, sonorous phrases; it needed balance and imagery, for he had the heart of a poet. And I was not surprised, the other day, when Marjorie Wright mentioned a collection of his verses. He had never thought enough of them to have them published. More than that, he had always been opposed to publishing them."

This definitely explains a lot about why the quality of Weird Tales was always so high as a whole. He knew exactly the sort of story that would speak to people.

"Farnsworth's sense of humor covered the entire field, and with his knowledge of French, Spanish, German, and I think, Italian, as well as Latin, that field was wide. No matter what you dredged from a quip, you did not have to supply blueprints to get a hearty laugh from Farnsworth. There was nothing too subtle, nor anything too bawdy; in a flash, he would switch from jeux d'espirit, as delicate as Hungarian Somlyoi, to a barrack-room jest as rugged as Demerara rum. To say that the man was no pride is the ultimate understatement."

This speaks of a man who knows the common man very well, and knows how to connect with different people of different places.

And, in case the above quote might give the impression that he had a dirty mind, Mr. Weinberg is quick to defend Mr. Wright.

"I never knew a man whose mind was farther from the gutter; it was rather that, like Rabelais, a jest was a jest, no matter where you found it, and an unusual rhyme was music, regardless of the context. He reserved these flights of fancy for stag gatherings; in mixed crowds, he was scrupulously proper in his humor. He soared to the heights, he plumbed the depths of English and other languages, and kept his mind clean--nor was his a sheltered existence. Unlike many of his contributors, he had met and known many people and many types and many places. And each fed that agile fancy."

This was very obviously written in a different time about a very different world.

Most of the chapter on Farnsworth Wright is spent by Mr. Weinberg giving the clearest picture of his long gone friend as he can, and I would say he succeeded terrifically. One might say he was dealing with kid gloves talking about his old chum, but Mr. Wright had been gone nearly 40 years by the publication of this work and there were certainly few left alive to give an accurate account of him. It wasn't as if others were beating down the doors to write books on the subject.

What this shows is just what a unique individual Farnsworth Wright was, and I am thankful he wrote it. This work really gives us a window into the incredible success and influence that Weird Tales would eventually have. There was no magazine like Weird Tales, and there was no one else like Farnsworth Wright.

This is emphasized when Mr. Wright allowed Mr. Weinberg to read manuscripts for the magazine. You see advice that has since become standard outside of the writer's workshop set for those who want the best stories they can get.

"Another half dozen manuscripts, and I sat up with a whoop! Farnsworth had been right. The vitality, that indefinable something which makes a phrase live, makes a paragraph glow, makes an entire story sparkle, had put me on my feet. He chuckled, and he did not glance over the dead ones. He knew that I had learned a lesson: that a writer deserves exactly as much attention as his manuscripts compel, and not one bit more. And he went on to say, "It's really not necessary to read each dud to the horrible ending. If they don't come to life within the first two pages, they'll remain zombies to the finish."

This is the beating heart of pulp writing, and good writing as a whole.

"You may think that Farnsworth was radical in his methods of reading manuscripts, and cynical in his disposal of authors and their work. this was not the case. He was merely honest and realistic, refusing to waste his time on causes which according to his experience and logic were lost from the start. In the time saved by this realism, he went to great trouble to analyze "living" stories whose mechanical details were wrong, and to suggest revisions to make them acceptable. This was, he confessed, a thankless task on the whole, one which often brought him a letter packed with indignation and fury; but once in a while, the author cooperated."

As a writer myself I can tell you that I do prefer Mr. Wright's approach. If a story should be scrapped, I'd rather just hear it instead of trying to save a corpse from drowning. Editors are, in fact, attempting to make your story the best it can be. Why argue with them, unless they have no idea what they are doing in the first place. Mr. Wright, as can be seen, clearly knew what he was doing. Why argue with the best of the best?

There are a few other stories of Mr. Wright's editing prowess, such as when he first discovered CL Moore and took the day off to celebrate this great discovery. This is clearly a man who lived for the passion of what he did.

From Mr. Weinberg's explanation, they all appeared to have quite a lot of fun playing with language and discussing literary subjects over the years. From all description, Mr. Wright appeared to be rather jovial in his love of the arts.

"Farnsworth, however, was no solemn mentor; scholarly, talented, with a musical background as least as full and rich as his literary and linguistic background, he was never on the lecturer's platform. We, the group, met as equals; each contributed a specialty, and expanded in the appreciation of the others."

A professional, but a good and loyal friend. It was almost like he fell into the completely wrong industry!

The author also includes a letter written by Mr. Wright's wife who describes even more about the man. Suffice to say, there was a lot to him. How he became one of the most influential editors of the 20th century is clear in how much of a character he was. Compared to others of his age, and those to come, he was a man with a vision and a love for the arts. There was no a drop of cultist blood in him--something we certainly take for granted today.

His father died when he was four, yet he still had strong memories of him removing a sliver from his finger. He took care of his mother as best as he could. Mr. Wright was dedicated both to his family and to his friends. He received quite a few blows in life, but never lost his focus or his ambitions to do all that he could. He never lost his sense of wonder and zest for life, despite the disease that would ultimately take his life at a relatively young age.

Only in his early 50s, Farnsworth Wright's crippling Parkinson's Disease he had since 1921 had grown so bad that in the 1930s, he could hardly stand or walk without severe agony. By 1940 it had gotten so bad that he resigned from the magazine and endeavored on a surgery that was not so successful. He died not long later in June, as mentioned earlier.

It should not be emphasized how much Farnsworth Wright was instrumental to Weird Tales' success and much of the art that was to come in the century ahead.

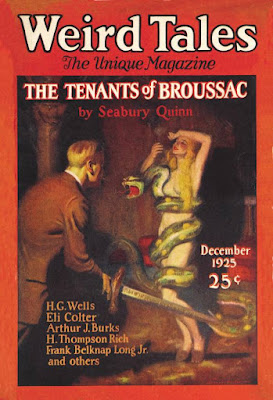

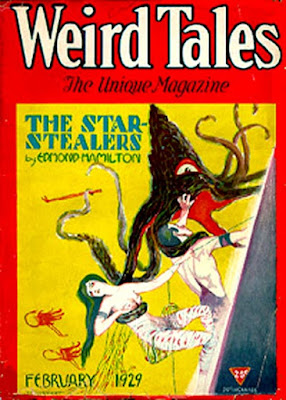

He aided in breaking out HP Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, CL Moore, Frank Belknap Long, E. Hoffman Price, Mary Elizabeth Councilman, Arthur J. Burks, H. Warner Munn, Nictzin Dyalhis, August Derleth, GG Pendarves, Edmond Hamilton, Donald Wandrei, Bassett Morgan, H Bedford Jones, Hugh B. Cave, Carl Jacobi, Robert Bloch, Henry Kuttner, Thomas Kelley, and Manly Wade Wellman, and kept writers such as Greye La Spina and Henry Whitehead published despite the lack of markets for their sort of stories. He also published other pulp writers such as Ray Cummings, Murray Leinster, Seabury Quinn, CM Eddy, JU Giesy, Otis Adelbert Kline, Frank Owen, Abraham Merritt, Gaston Leroux, David H Keller, Ralph Milne Farley, Jack Williamson, and P Schuyler Miller. On top of this, he started the commercial careers of influential artists such as Margaret Brundage, Virgil Finlay, and Hannes Bok, among many others.

One can not exaggerate how good of an editor he was, and how much credit he deserves for making the greatest magazine that he could possibly make. Weird Tales became what it did in large part to Farnsworth Wright.

That said, nothing lasts forever, and Mr. Wright's retirement and subsequent death (along with several of the above authors) meant things would have to change going forward. It did, but not so much by choice as by necessity of the shrinking market.

You see, pulps peaked in the 1930s in popularity and sales, but the 1940s was a downhill slide and contraction of the market (especially post-WWII) exacerbated by changing technology and new forms of media consumption such as television and comic books taking a chunk out of the market. Most of Weird Tales' decisions going forward were more about staying alive in trying times. The Golden Age was over.

And they got the best person they could for the job. The third and final editor of Weird Tales was actually Farnsworth Wright's assistant editor (and the only one who could succeed him), Dorothy McIlwraith. She ably dealt with changing market trends and kept Weird Tales afloat for over a decade and into the 1950s when there simply wasn't any market left at all. She deserves credit for that, even if she didn't keep the magazine as consistent as she did.

The elephant in the room is that she was more of a craft-focused editor than Mr. Wright, and was not as ingenious or creative as him, but few were. Instead, she focused on building a strong framework for the magazine to keep it afloat.

"Dorothy McIlwraith was a capable pulp editor who was not adverse to spending money to get quality material. the only trouble was that Weird Tales was the lesser of the two magazines she edited. Short Stories was the money-maker and the bigger name. Most of the budget went to its upkeep."

She might not have had the passion Mr. Wright had, but then again there appeared to be less writers with that passion, too. Many of the writers from the peak era had either died, retired, or moved on to higher paying markets. She could only run what she was submitted, and she was simply being submitted to less than Farnsworth Wright was. It feels a lot more like she was squeezing blood from a penny, though she did get quite a lot of blood out of such a small coin.

"Also, the war hit both pulps hard. Ms. McIlwraith did the best she could with Weird Tales but the best days of the magazine were past. In 1943, the page count dropped to 112 pages. In May 1944, another drop brought the page count down to 96 pages. In September 1947, the price was raised quietly from 15¢ to 20¢ an issue. In May 1949, the increase in price went to 25¢. All during this time, the quality of the magazine dropped. Dorothy McIlwraith got the best material she could. The one problem was that the authors who had made Weird Tales great were gone--either dead or moved up to better-paying pulps.

"In September 1953, the magazine went to digest size in a last effort to keep alive. The hope was a short-lived one. Its last issue was dated September 1954. In all, it ran for 279 issues."

I have heard tell at how many blamed Ms. McIlwraith for destroying Weird Tales, but that is simply not the case. She did not publish sword and sorcery, they claim . . . when most tapered off on the genre after Howard's death. She published no serials and instead much shorter stories . . . when they had limited space do to economic factors. It simply wasn't the 1930s anymore, and she could not roll back the clock.

It should really be emphasized that by this point their stable was either gone or dead and that they had no budget or much in the way of opportunity to build a new one. Not to mention, there was competition now from other mediums.

Despite all this, these final years were not a disaster. Weird Tales still outlived many of the other pulps, including those such as Unknown which slipped fast into obscurity while the original Unique Magazine trucked onward.

Many old writers who were not dead or retired did return to the magazine. On top of it there were many names that climbed on board while she was editor. Some names include Manly Banister, Anthony Boucher, Ray Bradbury, Joseph Payne Brennan, Fredric Brown, Stanton A Coblentz, Frank Gruber, Allison V Harding, Malcolm Jameson, Theodore Sturgeon, Harold Lawlor, Algernon Blackwood, HR Wakefield, Fritz Leiber Jr., Emil Petaja, and Margaret St Clair.

Some of the older authors such as Robert Bloch and Manly Wade Wellman even contributed more under McIlwraith than they did under Wright. In Wellman's case he put out the John Thunstone stories, reportedly a series she helped him conceive, which were some of the magazine's most popular. It was hardly a dry well of creativity during these times. There were just less of them than there was in the Golden Age.

Those above names are heavy hitters, no matter who you are. With this stable, as well as many one-off contributors, like always, Dorothy McIlwraith managed to keep Weird Tales alive when the competition died off around it.

While the magazine was less successful as it went, it did manage to keep enough thrills in its pages to keep the flame alive. Nonetheless, steam did eventually run out of the industry at the same moment the magazine was winding down.

Those above names are heavy hitters, no matter who you are. With this stable, as well as many one-off contributors, like always, Dorothy McIlwraith managed to keep Weird Tales alive when the competition died off around it.

While the magazine was less successful as it went, it did manage to keep enough thrills in its pages to keep the flame alive. Nonetheless, steam did eventually run out of the industry at the same moment the magazine was winding down.

"Death came in September 1954. Dorothy McIlwraith had done her best to keep Weird Tales going under a limited budget and under policies not always in the best interest of the magazine. But a general lack of interest in weird fiction and too much competition finally did Weird Tales in.

"The magazine was finished but not so the fiction. Hundreds of stories from Weird Tales have been reprinted from it, beginning with anthologies edited in the 1920s through books being assembled today. It still remains the single most important source of modern weird fiction ever published. As long as a single story is reprinted, the fiction of Weird Tales will live on."

Ms. McIlwraith, oddly enough, retired from her editing post from Short Stories (which itself died not even five years later) and left the company after Weird Tales folded. She worked one more decade in New York publishing before she left the industry to a farmhouse in Ontario, Canada in 1964. She died in 1976 at 84 years old.

Its legacy would go on regardless, in the book itself is even an entire chapter devoted to sharing memories for those who were involved in the magazine. The covers and interior art, as well as The Eyrie (the reader's letter section) merited entire chapters, too. The influence of Weird Tales really was something else. What's more, is that it was not led by Fandom but by normal readers. Its success and lingering afterwards came from writers who deliberately aimed for your average Joe, the lover of weird stories. This is how the influence spread so far and wide and touched so much. There is precious little else from that era as effective as it was.

Most of this success came from the passion displayed in its pages by professional creators. Writers, editors, and artists, all made it what it was.

"Farnsworth Wright had many jobs other than editor of Weird Tales. He also served as art editor, blurb writer, and general make-up man for the magazine. While Bill Sprenger was in charge of finances, Wright did all the rest of the work. Wright possessed all of the right characteristics for a blurb writer, He had a boundless enthusiasm for the stories he published and delighted in telling them, either to friends of in print. He wrote his blurbs with an infectious excitement that spurred on even the most jaded reader to investigate further."

That is where we should leave this series off, I think.

While there is much to complain about in regards to where the industry went post-1940, the important point is to remember what worked from that Golden Age when the pulps were at their peak of quality and popularity.

While Fandom might have done tremendous damage to the arts over the 20th century in their quest to create Utopia, there are still avenues to real artists, writers, and general creators to forge their own path for everyone else. Truth finds a way.

The magazines might be over, but much else is, too. Those days are gone, and they're not coming back. Much more lies ahead for the rest of us.

Today, in the 21st century, the old publishing industry headed by Fandom cultists is on the way out. We have new roads ahead of us whether it be in the eBook world or in crowdfunding. There are exciting times ahead, making the future as uncertain as ever. The things that led Weird Tales to its death are not obstacles anymore.

So while those old days fall away, we still have the good times; we still have the greats preserved and ready for rediscovery. We have a path forward, connecting to the past to bring us to the future. Fandom is dead, its power sapped, and crumbling away. But art continues on anyway, despite them. It always does, doesn't it?

And so, must we.

No comments:

Post a Comment