Once again, we return with the second entry in our new series on Fandom and the destruction they hath wrought on their own scene. I hope you are ready for another dive!

It's been a bit of a wild week since the previous post, and the reaction to it wasn't as intense as I was expecting, but that doesn't mean there isn't still far more rabbit hole to go down. No, we still have 10 more chapters of this book to cover. Though even that isn't as straightforward as one would think because the lengths are wildly disproportionate and some of them feel like a lot of repetitive information was copy-pasted into them. Dividing this series up in a presentable format has been quite a pain, and far more cumbersome that author's other book. As a result, this series was more of a slog to compile than the previous two were. Either way, we're going to continue with the next instalment. This one is not going to be as heavy as the last one. I promise.

Today, we will be looking at the next trio of chapters. Much of these required going over much repetitive information covered in previous series, so I had to skim over some material again. If you've read the first series then you really aren't missing anything.

As I hinted, in this entry we will be going over chapters 2, 3, and 4. The first is entitled Prehistory which is about, you guessed it, the formation of their "genre" and everything leading up to it. Well, at least that's what it's supposed to be about, but we'll get to that.

First, I wanted to clarify a few things in case some got the wrong impression last week. The vitriol you read was 100% intended for Fandom and their hangers-on who maintain their makeshift sandbox. Perhaps it sounded a bit out of joint to one reading this from a third party perspective, but covering enough of this sort of stuff tends to heat the blood quite a bit. When you see what they've destroyed and yet act as if they had the moral authority to do it, one can get a beat heated. books like this are especially effective at doing that when you realize just how weak a lot of the justification for what they did was and how there is no leg to stand on.

I'm going to try to keep it as objective as possible, but the above should be kept in mind going forward. There is no other sort of person this annoyance applies to other than the group of obsessive Fanatics that warped a field of entertainment for their own ends. All I want is for non-fanatics to realize the boxes created for these "genres" aren't actually real, that the people who created them had no idea what they were doing, that new and upcoming writers can truly write whatever they want, and hopefully with this knowledge we can bring back readers and stifled potential that was chased away over the years of Fandom's numerous failures.

After all, this is the ultimate goal: to widen the field, not narrow it. If your goal is to narrow a field of art then you are working against its natural purpose. You are actively chasing away opportunities to grow. Fandom has been gatekeeping the entire field since the late 1930s, and it has done nothing but lead to the laughable state of today. This happened because they were let in the door to do it. None of the normal readers asked for them to do this, but they did it anyway. And now it is the lowest selling "genre" by far.

Normal people deserve better.

|

| From 2016. Things haven't changed much. |

So without further ado, let us continue our dive into chapter 2. We've got much to catch up on and not an infinite amount of space to do it in.

The main issue with covering chapter 2 is that most of the information was already dispensed in the first series we covered years back. In other words, we're going to have to skim over a good bit of it. Should you want that information then I suggest going back and reading the first series again. It was definitely delivered better in Mr. Lundwall's other book. This time, however, we are more interested in the framing being used.

As such, this is how Mr. Lundwall begins the second chapter:

"The pursuit of the origins-of science fiction in the mists of the dim and distant past has always struck me as a little bit funny; it is following an established academic tradition whereby when someone asks you about something, you immediately have got to turn around and look behind you, to see where it started."

. . . Why is this "a little bit funny," in any way? This is literally how every tradition since the dawn of time works. If you don't have a history to trace your lineage from then you are making it up as you go along and therefore have no claim to legitimacy through history. You are building on nothing and therefore have no sturdy base to start from.

I can agree with this take for his "genre," but then it sort of goes against the whole concept of this book, which is meant to be the Koran for 20th century philosophy, only instead of texts it is made up of poorly disguised propaganda pamphlets that contain no attempts at eternal truths, but merely the Here and Now. That wouldn't make this a book that attempts legitimacy, but one that just assumes it is legitimate because of the year in the copyright information.

That isn't a formula for building anything and, what do you know, it hasn't.

"For science fiction, which is mainly based on the future and what it might bring, this tendency seems to me somewhat odd. It is an attempt, I think, to make the subject respectable, providing an image for it, because you are not supposed to suddenly produce something new, it is very upsetting, you are not supposed to do that, you are supposed to prove that it came from somebody respectable with a long gray beard yesterday. In literature, age means respectability, no matter what the contents."

How in the world are you expected to know what comes in the future if you don't understand even a little about the past? By what basis are these guesses of future life even being made? "Respectability" doesn't come close to it, especially when this supposed genre doesn't have anything resembling a tradition behind it. It's more that you can't hope to create something new if you don't even know if it was already created in the past. It's all been done, and the sooner you understand that the sooner you can build on your ancestor's accomplishments towards something new.

And as for the dig at age, that is merely a Baby Boomer calling card. Everything before you was stupid, your parents are unhip and just don't get it, but those guys on the TV box and corporate magazine space that tell you how special you are? They're the real ones you can trust. Mom and Dad are wrong about their traditions and history leading to you living in the most prosperous place on Earth at the most bountiful time. You know who is right? The group of people that harbored sex offenders for decades and still had the gall to lecture normal people on ethics.

Ironically, history isn't going to be very kind to this lot. When you start a new tradition built on hating tradition, how do you expect your work to last? It won't, and it already is falling apart as we speak. This is Fandom's legacy.

This is a remarkably ignorant passage to start a chapter on "history" which probably should have been pointed out by the editor. Of course, it wasn't. It looks as if OldPub editors were no less sloppy back in the 1970s than they are today.

And this is one of the stronger chapters in that regard. So you know we're in for a ride. Later chapters can go right off the rails.

So let us highlight the following passage, which is his, and Fandom's, entire thesis statement. Emphasis mine:

"Science fiction is, actually, a very modem phenomenon, the result of the latest century's industrial, scientific and social revolution, and even though the ancient Greeks busied themselves both with Moon travels and robots, they did not live in the atmosphere of constant change that is so characteristic for our century, and which is the essential thing about (and the motivating force behind) all science fiction. Science fiction is, if perhaps not the only contemporary literature, undoubtedly the most typical literature of our time, the most sensitive indicator of social and intellectual tides. This is, of course, no new phenomenon."

The explanation and definition boils down to "we are new; they are old" and that is why this new "genre" exists. It's a way for 20th century egoists to reward their own "progress" and advancement into an enlightened age above all others. All this, even though, essentially, none of this is actually new, at all.

And yet somehow this is an important "genre" deserving of book shelf space, but only because we inserted 20th century materialism as the driving philosophy instead of tradition, history, religion, or much in the way of non-nihilistic metaphysics. This pared down "genre" deserves its own classification away from the riffraff. Because it's going to change the world.

It didn't, but we already know why. Being based on a dated philosophy from a forgotten time meant it could never last long. And it didn't.

Look, either it is an already existing genre, or it's a rootless invention and can be blown away with even the weakest summer breeze. You don't get to pick whichever one is more convenient for you. Genres aren't clubhouses or secret societies.

Though, perhaps that is why this one is already dying.

"The chansons de geste of the Middle Ages faithfully reflected the rigid feudal society of its time, and later, when the power of the Church and the nobility was reduced due to social reforms and upheavals, the picaresque novel appeared as an expression of the skepticism that was born out of the new times. The fantastic novel, in the form we know it, appeared first during the Age of Enlightenment, with political satirists like Voltaire (Micromegas) and Lud-vig Holberg (Nicolai Klimii Iter Subterraneum), at about the same time as authors like the Marquis de Sade explored the subconscious in works like One Hundred Days in Sodom and Matthew Gregory Lewis with The Monk. It is interesting to note the pyramidal success of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's novel Frankenstein, which, published in 1818, apparently gave voice to widespread misgivings toward the industrial revolution with its theme of forbidden knowledge coupled with Shelleyian romantic ideals."

Again, the only change is the emergence of a philosophical system that you personally like. This doesn't suddenly create new genres. Genres are based on eternal truths and deep longings from the audience, which is why they have such simple labels anyone can connect with. They are very simple things, which is why none of them need books to explain themselves.

None of the above is actually anything new other than the typical modern doctrine that more or less is summed up as New Thing Good. This doesn't suddenly change reality and allow your personally philosophy its own genre set apart from everything else and deserving of being enshrined by your High Order in the larger publishing industry. But as we all know, one of the definitions Mr. Lundwall gave us last time was that this is loser fiction, so that goes a long way to explaining all of this. It is an attempt to brute force itself into the wider culture.

That would surely explain a lot of Fandom's behavior over the years, and why they so consistently fail at this.

"This literature was— and is—typical of a world and a time in rapid change, with insecurity and great hopes and misgivings for the future. Science fiction of this type would obviously have been unthinkable in ancient Greece."

What in the world are you talking about? Anxiety over the future is not a modern invention. The whole reason the study of philosophy and theology exists is to understand our place in the world and why we exist. The more we can understand the past the more we can use it to apply to future problems and overcome future hurdles.

This attitude is where that nonsense Arthur C. Clarke quote about Magic essentially being Science we don't understand came from. You have so little respect for people who came before that you think they are dimwits due to the age they were born in while you are a genius because of your birth year. Not only do you not even understand what Magic actually is (Hint: it has nothing to do with Science), but you don't even understand your ancestors. They were and are made of strong stock. To dismiss them so readily shows nothing but arrogance.

And here you are enshrining your ignorance as an intelligent observation which is based on nothing but your own ego. Mr. Lundwall really makes a habit of this.

I really hate the fact that we're still only in chapter 2.

"In Sweden, some enthusiastic scholars seriously maintain that Dante Alighieri's religious allegory Divina Commedia was the first real science fiction work, with the radiant Beatrice the first astronaut. Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress has also been nominated to science fiction's hall of fame, which, needless to say, strikes me as being somewhat odd."

A lot appears to strike Mr. Lundwall as being odd, especially when the work isn't a pure materialist fever dream and allows unbridled imagination to tell a story. Remember, you're not allowed to have those in this field. They created a whole category to shove your nonsense into so they can keep their side of it pure.

For a genre supposedly based on "Sense of Wonder," as they call it, no one in it really seems to understand the first thing about wonder.

"Cyril Kornbluth said in The Science Fiction Novel (1964) that "Some of the amateur scholars of science fiction are veritable Hitlers for aggrandizing their field. If they perceive in, say, a sixteenth century satire some vaguely speculative element they see it as a trembling and persecuted minority, demand Anschluss, and proceed to annex the satire to science fiction."

Here we go.

The Nazi nonsense being brought up again aside, this passage is literally what this entire book is. There is no solid foundation for anything here except taste. Good things I like = Science Fiction; Bad things I don't = Fantasy. We take and claim what we want and ignore what we don't to get the perfectly concocted Genre of Modernity the will guide man to utopia. Let us invent even more nonsense subgenres to split everything else up further: as long as the core purpose of indoctrination into modernity remains.

The fact is that all of this actually is just one genre--just not the one Fandom is trying to build for themselves. That one doesn't actually exist.

"Icaromenippos is, strictly speaking, a satire of the conventional type, and science fiction only by the situation (the Moon journey and the visit to the Gods). The plot is fantastic, but it is certainly not speculative in any way."

What does this even mean? It's nonsense. Mr. Lundwall doesn't believe in Greek Gods either, yet I'm sure he'd be the first in line to claim The Iliad as Science Fiction and then bend over backwards trying to square that circle. I've seen it happen before. One of them can be used for scriptural purposes, the other can't. That's all it comes down to.

This all one genre, folks. It's simply not his.

"The real breakthrough for science fiction came with the late industrialization, when the universe suddenly threw its gates wide open and nothing was impossible any longer. The holy machine was placed in the high seat, and with its help one could accomplish absolutely anything. This was the time of the unlimited belief in progress, and Queen Victoria sat with the sleeping lions at her feet and watched benevolently how the sky was darkened by smoke from railways and steelworks."

This aged well. Or it would have had the God of Progress not fallen out of His bed and crumbled to dust on the floor during the back half of the 20th century. No one believes the above anymore, if many ever really did to begin with.

Industrialization doesn't create new literary genres because it's not an eternal truth, just a thing that happens. And as it turns out, it was a thing with a limited shelf-life that was but a blip on the history of humanity and the wider universe. People can still tell stories with or without it, just as they had for an uncountable number of years beforehand.

And they will continue long after the next invention comes around.

The entire chapter is an attempt to see if satire can be pulled into their made-up genre because they have no precursor. The fact that there is no precursor because there was no materialist propaganda before they came around is not even thought of as a possibility. And this is why the clubhouse failed to make much traction: it isn't based on any solid foundation. Just wishful thinking.

And that's where chapter 2 ends, with a mistaken assumption about the nature of reality that could only have been made at the time it was written. It does not take into account how these changes in industrialization might have changed the way we operate, and should probably be better studied and understood. No, rushing ahead was always the modernist way. And look where that has gotten us. Blind progress for the sake of progress has left the western world adrift in its own atomization, unsure of how to break out of it.

Not even five years before the publication of this book did Marshall McLuhan write the following in The Medium is the Massage:

"Printing, a ditto device confirmed and extended the new visual stress. It provided the first uniformly repeatable "commodity," the first assembly line--mass production."It created the portable book, which men could read in privacy and isolation from others. Man could now inspire--and conspire.""Like easel painting, the printed book added much to the new cult of individualism. The private, fixed point of view became possible and literacy conferred the power of detachment, non-involvement."

And this is exactly what Fandom did--use their medium to be weaponized against the audience. Their "individualism" turned art inside out, and without any reflection led to the torpedoing of their own playground in the years to come.

There was no utopia coming for one who saw the signs on the wall, though those who specialized in the "future" completely missed McLuhan's entire point, even as the end result of the 20th century has proved his assertions entirely correct. What arrived wasn't utopia--it was the complete opposite result of that.

I'm not going to pretend people like Mr. Lundwall should have known this was going to happen, but considering their entire field missed out on this observation it should raise more than a few eyebrows. As I've said, for a group priding itself on understanding the future, they sure weren't very good at doing it. When you don't understand your past you are doomed to repeat the most unsavory parts of it. No wonder the field is dead.

And we're all probably better off for it.

Unfortunately, the next chapter is about Utopia and is a rehash (really more of a precursor) to the similar chapter covered in the previous series of posts. About the only difference is the level of youthful arrogance and sneering that would have been left of the cutting room floor had the editor of this work had an ounce of class.

But we shouldn't expect that much from Fandom. Time and time again they have proved they know little more than charging off cliffs like lemmings while smirking about being winners the entire time. More and more it appears that Mr. Lundwall's earlier claim about it being loser fiction has merit. They sure like to live up to the name.

That is how you get passages such as this:

"It should be noted that this novel was written five years before Hugo Gernsback, the "father of modern science fiction," even was born. Actually, Oxygen och Aromasia was at least sixty years before its time, being more modern than any science fiction written in the U.S.A. before 1930, both in imagination and quality of writing. Lundin even considered women as human beings, something that didn't dawn upon most sf writers until the middle of the twentieth century."

Disgraceful and juvenile, the lack of respect for the people who created his job position is palpable. And yet we're listening to him because the same Fandom cultists told us that being ignorant about your past is a positive trait worthy of getting you job positions. And the book doesn't get better in this aspect, either.

Here is the issue: when you are professing to write a history on something it is your job to appear as neutral as possible. Is true neutrality really possible? Maybe not. However, there is a level beyond attempting to tell the audience what people you disagree with were doing and badmouthing their entire existence. If anyone read this book and thought this was in any way an attempt at being unbiased they are probably the same cultists that gave this man a platform to write this in the first place. It is hard to imagine actual adults behaving this way, and yet this is reality. This is what Fandom is--a bunch of adult children.

The book is filled with childish jabs like this, proving that our author should have been shoved into more lockers than exist in Sweden. I couldn't even imagine someone being this needlessly hateful in the public space. I highly recommend reading this book if you want to see a cultist nerd compare Plato to the Nazis, because professionalism doesn't really exist in this field, just as this "genre" doesn't exist. It's all a smoke screen for shallow philosophy.

"This, in a nutshell, is the theory of Utopian life and code of conduct, not only for More's novel, but for all Utopian societies: Think what you wish, but think right."

Not even a few paragraphs before this passage did he literally use the term "the Third Reich of Plato" to shrug off an entire branch of philosophy at the root of the western civilization that allows him to even exist. Materialist cultists do not seem to have enough self-awareness to fill a thimble, but for some reason we grant them room to do this sort of thing to destroy all that came before. Mind you, he destroys those things because the writers don't think right.

Forget thinking right, Mr. Lundwall-- just attempt to think.

"In our time, the Utopian novel has found a worthy successor in works like those of Mickey Spillane, with their almost erotic dreams of fulfilled sadism."

Never mind, I guess that was an impossible request. Silly me.

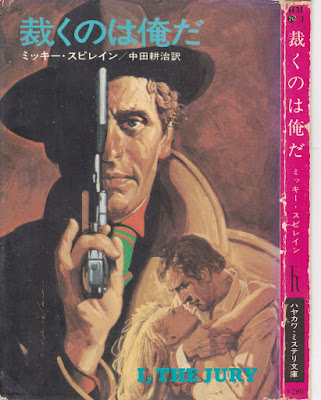

Mickey Spillane's stories are about men driven to the edge in a dangerous world. Their appeal is in the moral battle the protagonist has with attempting to remain human or falling into the dark world of their antagonists. The very first Mike Hammer book, I, the Jury, is about just this. Too many people misjudge this one as a "mystery" due to myopic genre thinking that they miss the point that it isn't a mystery at all. The final line hints that Hammer figured out the killer's identity long ago but was unable to make a judgement call in regards to that knowledge because of everything that had happened since the story began. This is why the last words of the book being "It was easy" hit so hard--because it clearly wasn't at all. The entire book is about the main character on the edge of despair and fighting it off as best he can by seeking justice. Then he has to make the ultimate sacrifice: is Justice more important than what he wants?

There is nothing admirable about the world Mickey Spillane employs in his stories. If anything, they are almost dystopia tales about urban hell. That someone like Mr. Lundwall could miss something that obvious should say a lot. But then again, it is a non-materialist reading of a story written by a non-materialist. Cultists tend to have problems relating to such things.

Regardless, it isn't utopian in the slightest. This is completely unlike anything Mr. Lundwall peddles. He is actually very much in favor of utopian fiction--just the barely disguised kind.

The irony of all this is, of course, is that Mr. Lundwall's ideal "Science Fiction" consists of materialist fables that attempt to teach the correct thoughts and attitudes in order to brainwash the audience into Being Better. He describes Utopian stories as being naked power fantasies of perfect worlds from flawed people when he is no different at all with his preferences. If anything, he only hates that Utopian fiction gives the game away instead of barely disguising it.

"Science Fiction" is meant to weaponize modernism while wrapping it in the "progress" of the industrial revolution in order to advance humanity to perfection. We live in a new era, so we need a new sort of fable for Advanced Humans. This is the thesis given.

The Modern Age is here! Everything is going to be different now.

That surely is what it must looked like to certain folks in the early 1970s. It didn't work out to be like that, though. The modern era's siren song of endless progress to utopia ran out with the 20th century. Now we're just left with out of date baby boomer dreams from people who have no relation to our reality, whether it be the past or our current future. That world is over and done, and it is never coming back.

That is, if you ever believed it existed to begin with. Audiences didn't want it in the 20th century, rejecting leaflet fiction when pulp adventures had been thrown out by those in charge. They certainly don't want it now after decades of plummeting sales, a dying OldPub industry, and the return of adventure fiction to the forefront of NewPub.

"Science Fiction" never existed except as a scam meant to sell you tracts to old outdated worldviews that haven't been relevant since the time Munsey learned how to produce pulpwood magazines. And it wasn't even relevant then either.

In fact, the only higher thing this lot can seem to stomach beyond Science worship is base pleasure, such as wanton sex. I'm not kidding.

"The Utopian novel is escapist, as all dreams of the unattainable must be, and the science fiction writers of today are all too practical to go on escapist Utopian sprees. One of the very few exceptions I know of is the noted sf writer Theodore Sturgeon's novel Venus Plus X (1960), which depicts a Utopia in the classic sense, complete with universal brotherhood, understanding, intelligence, love and no dissenters in sight. That the novel still manages to convey a message is entirely due to Sturgeon's obvious skills as a writer, plus the fact that this particular Utopia is built upon sexual and moral standards that in themselves make the novel interesting. Apart from that, this is Schlaraffenland all over again, and no beautiful machinery can make it credible. The societies created by other sf writers are far, far removed from this."

"Interesting." Sure. Whatever you say, Mr. Lundwall. I really do not believe this book was edited at all. He can only see storytelling in different shades of propaganda, and it makes every opinion he has as predictable as the last.

"Imagined societies are still created in science fiction, but they are far from the escapist Utopias of yore. Robert A. Heinlein's and Isaac Asimov's highly complicated future societies are good examples of this. They are, on the whole, better than the societies of today, just as our world on the whole is better than that of a hundred years ago, but they are not perfect. No world will ever be perfect because man isn't, and no deus ex machina in the form of a brilliant new religious concept or some wonderful mechanical gadget will ever do the work for him."

And neither will a made-up genre of fiction, as we have seen from the absolute failure that is supposed to be "Science Fiction" and its Fandom.

At what point after near a century of failure, an inability to sell, and being framed on a flawed belief system that no society has ever believed on a wide scale, do we admit that it is time to stop allowing these geeks to play pretend with reality and hogging resources that could be better spent on anything else? Like producing reprints of old Buck Rogers comics or reprints of lost pulp classics. At least those have value outside of their time and place.

Even talking about this is a waste of time. I'm only doing it because I need to hammer this in: "Science Fiction" is a lie. It is a scam meant to deliberately trojan horse a broken worldview into the populace that is incompatible with reality and humanity despite ostensibly being a genre about them.

Here is more proof:

"The English professor John Ronald Reuel Tolkien's epic trilogy The Fellowship of the Ring (1954-55) probably comes as close to a Utopia as anything that has been written during the last fifty years, with its innocent Rousseauian escapism, but even here dangers always lurk in the shadows, threatening to tear the gossamer security into fragments at the first sign of weakness. Also, the story evolves in a mythical ancient past, well before man. When man is mentioned, it is as something threatening, something that will cause the destruction of the fairyland. Utopias, the science fiction writers seem to say, cannot exist. If they, notwithstanding, should exist, they could never work. And if they, against all common sense, should work, they would not be of any use anyway."

There is no reading of The Lord of the Rings that could miss the point this badly unless it was another one of those sub-room temperature IQ "Orcs are people too!" screeds. That no one thought to edit this or tell Mr. Lundwall how stupid this assertion was, is telling.

This is the quality of thinking OldPub pushed on the field while simultaneously elbowing out pulp masters like A. Merritt once they died or former darlings like A.E. van Vogt once Fandom decided they weren't of use to them.

Now ask yourself why anyone would willingly publish something this outright dumb unless they weren't attempting to sway public opinion.

And what are they trying to sway it towards?

You already know the answer.

For the third and final chapter we are looking at today, we are also covering a familiar topic. I am unsure how much of this material Mr. Lundwall reused in his second book on the topic, but it appears quite a bit. This new chapter is entitled The Air-Conditioned Nightmare and deals with the anti-utopian story.

Given that we just dealt with utopianism, you might as well just cop and paste many of the same points we just went through.

This chapter is just more of the same. Since we also already talked about anti-utopian novels in the last series, I'm just going to skim this one over. There is no point repeating myself or Lundwall's same observations over and over. It's enough that I already read the other book on this topic. Instead, I will drag out some of the quotes which strike our interests.

"Many science fiction writers are incurable misanthropes. This might be the result of an uncommonly pessimistic inclination or a general perspicacity, but the fact is, that few modern sf writers have found reason to regard the future with any great hope."

Yes, after the pulp era, "Science Fiction" became known as the pessimistic hopeless side while "Fantasy" came known as the fluffy bunny delusional side. What would you expected when the sides are divided only by 20th century materialism and stale tropes? There isn't anything to look forward to in such a world aside from base pleasures.

Materialism on its own is a hopeless worldview which offers nothing but continuing existential agony in between bouts of sugar and alcohol binges. There is no brighter future ahead that doesn't consist of pleasure domes run by, I suppose, robots. Without the false god of progress to hang your worship hat on, what else is there? The passage of time since the date this book was written has shown us what: there is nothing else.

No wonder the "genre" fell into despair in record time, once it ditched its pulp roots and tradition. Reality hit them like a freight train.

"The future will turn out to be just like our own time, they observe—only worse. And then they summon forth a hell on Earth where the citizens are kept at bay by Thought Police and the big industrial trusts rule the people with a more or less obvious line of hard advertising, toward ever-increasing consumption and consequently rising opulence for the shareholders. The social dreams of the Victorians have been exchanged for scathing social criticism that, while most often based on cold, hard facts, sometimes topples on the borders of defeatism; the latter is commonly known as the "New Wave" syndrome of science fiction."

I don't even know how to reply to this, because all of it is happening in the world right now at this very moment. Perhaps this is why "New Wave" was the only real blip on the radar after the pulps to speak to anyone outside of Fandom. Possibly because it was more than just blatant social engineering propaganda. If it was written by feds, as those like Mr. Lundwall suggest, then they were a good deal more accurate and speculating on the way things would be than anyone since the pulp days. I thought that was the purpose of the genre, or are we playing dodgeball definition again? Perhaps that is why they were so hated.

Regardless, Mr. Lundwall's terms are wrong. "Defeatism" is not the process of logically deducing things out. That is is called being realistic. "Fantasy" is the process of pretending reality doesn't exist in order to suit your own agenda.

Much like this book.

"This was in 1949, when the author looked back at the second World War and began to fear for the probable evolution of the totalitarian state. Today, more than twenty years later, the dictatorate is usually more discreet—on the surface, that is—and the science fiction writers hardly expect the future dictators to use the same means as Big Brother of Orwell's novel. [. . .] Orwell is hopelessly out."

What a surprise, this is wrong.

Because, for a non-existent genre supposedly based on predicting the future through Science, "Science Fiction" writers are terribly bad at doing it. That might have a little to do with the core philosophy behind their assertions being based on a provably incorrect philosophy that has worn out its shelf life, but maybe it is just that most of the people who choose to write this stuff have horribly high opinions of themselves with egos as undeserved as the shelf space they stole from pulp masters. Fandom loses yet again.

Who really knows? Either way, they have no authority over anyone.

Lundwall then goes on to describe the then-growing consumerist culture of the time and lists a bunch of forgotten novels that satirize it, seemingly unaware of how consumerism and government control could possibly be tied together to form a bigger stick to hit people with. It wasn't around in Orwell or Huxley's time, and yet both of them managed to get closer to the mark than those who wish to use social science and loopy gadgets to make corny jokes and commentary couched in satire with the intent to take aim at their perceived political enemies instead. Missing the forest and the trees in one fell swoop.

This stuff has been forgotten because it's so obvious and clunky in its ham-handed messaging. This is what happens when the "genres" needed to be separate, because none of these writers understand Horror nearly as well as those older writers did. Lovecraft ran in "Science Fiction" magazines, was the face of the World Fantasy Award, and today is primarily known as a Horror writer. I'd say he was more than a bit closer to the mark than those who usurped him, especially considering his influence that lasts to this day.

Looking back at the passages Mr. Lundwall provides for these works that are "better" than Orwell would make anyone's spine shrink back into their stomach. They have aged so very poorly. Apparently Fandom agrees, too. Because they have not gone out of their way to keep any of this in print, even though they rule OldPub with an iron fist.

Prepare yourself: it gets awkward. Here is a future where coupons rule the world. I am being completely serious.

From J.G. Ballard's "The Subliminal Man":

"A large neon sign over the entrance (to the supermarket) listed the discount—a mere five percent—calculated on the volume of turnover. The highest discounts, sometimes up to twenty-five percent, were earned in the housing estates where junior white-collar workers lived. There, spending had a strong social incentive, and the desire to be the highest spender in the neighborhood was given moral reinforcement by the system of listing all the names and their accumulating cash totals on a huge electric sign in the supermarket foyers. The higher the spender, the greater his contribution to the discounts enjoyed by others. The lowest spenders were regarded as social criminals, free-riding on the backs of others."Luckily this system had yet to be adopted in Franklin's neighbourhood—not because the professional men and their wives were able to exercise more discretion, but because their higher incomes allowed them to contract into more expensive discount schemes operated by the big department stores in the city."

Never heard of this one? Can't say I'm surprised.

And when you take away the dated social commentary from the above, what are you left with? Oh right, nothing. Because there isn't anything else aside from the message. It's not really much of a story, is it?

What do you get from reading a piece like this in the 21st century? Nothing, because the only thing it offers is a grossly incorrect idea of a future we've already passed by and left in the dust. There is no eternal truth being built on.

But at least we can get talked down to by people who have no authority to talk down to us. It's always something when people who consistently get things wrong all agree they should still continue to tell others how correct they always are. It's really something else.

As Mr. Lundwall continues:

"The theme is, as I have said, widely used in anti-Utopian science fiction of today, and it seems as if the sf writers more and more now have turned from the earlier war and natural catastrophe themes to the results of our economic and environmental (mis)management and its impact on man. This way science fiction comes into the contemporary social and political debate, where it probably can do a lot of good through its unique qualifications for presumption-free evolution and behavior analysis."

Want to know why these stories have been repeating the same messages and themes for well over half a century at this point? The above quote is why. Just look at the terms "Presumption-free evolution" and "Behavior analysis" and you can understand why they are so often clueless and incorrect. They don't have to question anything, because they know.

Society does not evolve. Anyone who has been alive for the last three decades knows this as an obvious truth. There is no shining horizon or destination we are heading towards. It's just more of the same, forever. You can say they didn't know that back then, but that's basically the point. They didn't know, and yet continued to assume they did without ever admitting otherwise, and they still do so to this day. There is no utopia coming and it will not be guided to with spaceship accounting stories of x-theory tales. No one cares about your pet theory spurned from your fat ego. We are just driving in circles and have been for a very long time.

This was a faulty 20th century ideal based on a sudden boom in technological progress springing from the industrial revolution that led people to think we were closer than ever to fixing it all. We aren't, and we never will. Computers haven't made anyone smarter, and neither will the "correct" economic system. It simply doesn't work that way.

This isn't pessimism or "defeatism" or any other inane dismissal materialist utopianists love to spout at any criticism of their ideas. This is just reality. We aren't "progressing" to anything but the grave. Get used to it.

We can't expect the people of that time period of the late '60s to have understood this, of course, but we can know that there is no generation of human beings less capable of understanding basic human behavior than those born in the first half of the 20th century. Their life experience is too anomalous to take for any kind of standard, too degenerate, and too naïve, looking back on. It is like being straight edge and also deciding to be an expert wine taster: it can't be done.

They grew up in the material comfort of a typhoon of change they were constantly told (by people like Mr. Lundwall's heroes) that things were always changing and always in flux and we would be heading to a brighter tomorrow. Progress Is Inevitable, they'd say. This, despite the fact that they lived in a time period of prosperity and material growth that never had an equivalent in history, and never will again. They are outsiders to reality, and fashioning anything to their ways is akin to building a sandcastle by the waves.

It ain't gonna work, chief.

"Personally, I believe there is a far more intelligent and presumption-free debate going on in the decried science fiction genre than in many of the so-called conscious and, for most people, incomprehensible, cultural magazines that are embraced with such great benevolence by the critics. That these critics never have come in contact with the genre, other than the Sunday paper's comic strip section, is not the sf writers' fault."

As I've said, it's an insulated reality based on naïve trust of corporate institutions over tradition and inflated egos constructed around a misunderstanding of the time period one grew up in. All the people writers like this were trying to impress hated and wanted nothing to do with them, because they already had the social propaganda they needed in order to succeed. And, as I listed above, they were much better at it than supposed "Science Fiction" writers ever were.

So what use did these elites have for this small slice of behavior science stories that didn't understand behavior and used science to replace meaning? They didn't have any. Hence, these elites ignore them, which is something they couldn't do to the pulps. While OldPub still tries desperately to scrub that pulp influence from culture (something Mr. Lundwall and his cronies gleefully tried to do for them like some laughable combination of Igor and Judas), their replacements haven't even been preserved by Fandom itself. They've already moved on to the next fad, blissfully unaware that they aren't ahead of any game: they're following the frame of people who hate them and don't even care that their own supposed genre has cratered ages ago. Without a past or tradition to look back on, you might as well be walking into the ninth inning of a baseball game. It's already almost over.

No wonder no one reads any of this. It's all so pathetic when you stop and think about it.

Before we wrap it up, I want to include this take on Robert Heinlein's Starship Troopers, because it seems a bit backwards from everything else he has said so far, especially as one who doesn't understand the purpose of violence in stories at all.

"Now, this sounds like a thoroughly fascist state, and Starship Troopers has been subjected to a murderous criticism in sf circles, especially after it was awarded with science fiction's highly coveted Hugo Award in 1959. Myself, I would rather leave than love a country run along the lines of Heinlein's Utopia. But Heinlein has constructed his society with a logic that is rather seductive (you can accuse Heinlein for a lot of things, but never for faulty logic). In Heinlein's world the right to vote is thus a privilege that has to be earned with a specified, individual contribution of work. He proceeds, probably rightly, from the assumption that a person who is too lazy to earn this privilege also is too lazy to revolt against the established order of things. Thus, no "silent majority." If we look at our own society, the idea does not look so foolish. A great deal of the voters in the Western world do, as is well known, not vote so much on party platform as on the party candidate's appearance and morale, their own parents' political preferences and so on. A right to vote that had to be earned with hard labor in two or three years would probably be exercised with much more consideration. Heinlein's thesis seems, in short, to be that lazy people without knowledge of politics should not be permitted to participate in something as serious as politics. And who can dispute that?"

This is a very odd bit of clarity for someone who called Plato a Nazi a couple of chapters earlier. It is almost as if he is a bit picky and choosy over what counts and what doesn't. These principles bend in the wind. Perhaps because the only people Mr. Lundwall's generation have ever been skeptical of is their own parents that they just don't realize it. They would believe the television if it told them their fathers were all secret Nazis and needed to be turned in for reeducation. But Heinlein being a peer means, of course, that he has a point that those obviously incorrect old Greeks or pulp writers didn't. After all, they are old and Heinlein is new.

That's really all it comes down to, in the end.

But then our author goes on about the then-growing trend of anti-utopian propaganda pamphlets (he calls them novels) determined to make humanity hate itself.

"It is interesting to note the upswing of this type of anti-Utopia during the high points of the Cold War, showing the extermination of mankind in a thousand imaginative ways but always conveying a deep distrust in man's ability to behave as a thinking animal."

Thank you for illustrating why so many people moved on to movies, comics, television, and eventually video games, while sales plummeted for this very special genre during the same period of an apparent "upswing" of quality. You can get all of the above by watching Return of the Living Dead, a single movie from the 1980s. And that one is funny and attempts to entertain the audience in the process. Why in the world would you need piles of redundant novels that talk down to you in order to give the same basic message?

"I have already said that science fiction by its very nature must be a subversive thing, as it points out that there will always be changes, something that no establishment wishes to admit."

He's right, it is a subversive thing. It is subversive because it isn't meant to build, it is meant to separate and tear down, because it is based on an incorrect 20th century philosophy of the world that certain people held for five minutes of all of human history. It's dead because it cannot build, subversion ingrained in its DNA as simply being reactionary against whatever the "establishment" (a good boomer term, by the way) is perceived to be for. It can only be reactive.

This is a horrendously dated worldview by naïve people who think they can change the world through art. Weaponize that link between artist and patron and see where that gets you. All it has done is dilute the relationship between the two and invited in a class of poseur who demanded they be high priests of the sheep. Instead of equals, it has devolved into a battle of control. This change was an unmitigated disaster.

It is a very good thing we don't live in the 20th century anymore. Things to be thankful for.

"On the whole, the sf field has been spared the most mindless acts of the political censors. But with more and more writers turning to the science fiction story as a means to convey social criticism, it might be safe to assert that we will see more of this in the future."

Nope, didn't happen, and never will. I see writers that are part of the biggest "Science Fiction" writer's organization on social media advocating censorship and taking down free digital libraries because there's a penny they might not be given from the OldPub masters and their agents. They just want a few bucks tossed to them from their corporate masters. It's all a scam.

The principles they had when their enemies were in charge are long gone now that they are. Because they never had those principles to begin with.

"Nevertheless, the anti-Utopian branch, with its roots in ancient satirical writings, has always proven to be the most popular outside of the circle of sf aficionados, and most easily recognized by the critics as "Literature.""

Wrong, and laughably so. The most popular form of genre fiction is action and adventure stories, which people like Lundwall had to (and still try to) think of reasons to exclude from their clubhouse--a clubhouse which is already falling apart. Every example he's used in this chapter to describe his points (aside from about three) have been entirely forgotten by the mainstream and critics, and have been out of print for ages. Would they really be so if they were ever that popular to begin with? At least the pulps had excuses--deliberate and admitted sabotage from the editors that seized control. But this is their own work. Why can't they keep it going on their own? Why is it the lowest selling "genre" by far? That can't be right!

Well, partially because they are more preoccupied with genre purity. Fandom keeps making up new subgenre titles to describe things that already exist in order to file away what they don't like and keep it away from them. These are the important things to discuss, you see.

Of course, this also means we also have to separate and dilute said "genre" yet again. Now apparently average Science Fiction is called "Straight" Science Fiction as if anyone aside from baby boomers even remember these terms.

"Yet "straight" science fiction has never achieved the same impact on the literary scene. The reason for this might be that while the anti-Utopian novel is old as a literary phenomenon, the "straight" science fiction, depicting the future on its own terms, describing it as not necessarily better or worse but different, then taking this at its face value and trying to make the best of it, is new, and, therefore, somewhat suspicious."

That is a stretch meant to assuage the ego. People still write and sell futuristic military and space opera stories to great sales. There is clearly an audience there--but not the one that counts. Who even cares about the "literary" scene anymore? Just about nobody.

There is no literary scene that isn't run by megapublisher-backed writer's workshops. These workshops were created to sell product in the package of "art" or whatever corporate officers desire of their lapdogs. There is no art or entertainment here. Normal people don't buy literary fiction anymore. OldPub is dead. The future is not here.

"Personally, I find the anti-Utopian science fiction extremely interesting—but it shows only one side of the matter. It is anti but never pro; it gives criticism, but never even attempts a solution. Just as the Utopian story is escapist, its antithesis is defeatist; it must always be so. There is an unfortunate tendency in all literature to view all changes with the deepest suspicion and to put the worst construction on everything new. It would be very strange indeed if this did not pervade science fiction to a degree as well."

Here is the god of Progress yet again rearing his misshapen head. Being hesitant to change is being careful that you're not jumping from the frying pan into the fryer. There is nothing wrong with making sure you are on solid ground before taking a step through the threshold. It only takes one fall from a cliff to kill you.

I do agree with the rest of this assertion. However, I would posit that they are all Utopian novels. They all attempt to portray a world we are meant to react to, in order to shape out perception of the world we actually live in today. They are meant to mold your way of thinking to build the correct future away from the terrible present. Neither are actually meant to tell a story, or exist to entertain anyone. They both proceed with the same goal of getting you thinking about creating a better world, today! Then if you want to build a statue in their honor or put them in a history book or two they wouldn't object. It's the least you could do!

Audiences have never been particularly enamored with such things. they know what they're being talked at, not to. They're a lot smarter than Fandom thinks they are.

"No doubt many people in the year 2025 will look back to the wonderful golden days of 1971 when everything was so much better, and regard the new star ships and what-have-you with grave misgivings, feeling the ground rock beneath their feet. This is as it should be, and the anti-Utopian novel has done a lot of good by pointing out faults in society's machinery—but one should not stare oneself blind on this side of the coin."

. . . Do I really need to say anything to this assertion? Time itself does the speaking for me. All it does is show how good Fandom is at their own supposed "genre" of prediction.

"Basically, the anti-Utopian novel is just a way of saying (as Cyril M. Kornbluth puts it in The Science Fiction Novel) "I will show you what will happen if you don't listen to me and do as I say," as opposed to the Utopian message of "See here how beautiful and orderly everything will be if you make me dictator over the world." The difference is slight, and in the end they both come down to the same thing: an inability to face the present world. The anti-Utopian novel is interesting, and as a means of powerful social criticism, unsurpassed. It should be read with a pinch of salt, though. The future isn't all sour grapes."

There is no functional difference between the two, which is why I'm writing about the both of them in one post. They both exist for the same end goal, and are both glorified message fiction. Neither do much else other than attempt to educate the audience into the right thoughts for Progress. The only difference is that the anti-utopian novel obfuscates the obvious intent better, and only barely does so. That's all.

As you can see, Mr. Lundwall's expectation for the future is completely shaped by his time and place. Without any ability to look to tradition or understand the path that lead him to where he is or where he is going, he is left adrift in a fog of materialism and baseless optimism, certain that we will be in star ships by now. Fandom really thought like this.

This is the weakness of this whole supposed genre based on "Science" and why it was doomed to be nothing more than a dated fad among a tiny and shrinking clique of self-professed experts. It's embarrassingly naïve, at best. It has no place outside the 20th century, where it will eventually fade out, forgotten by the mists of time. And that's precisely what is currently happening.

Good riddance.

And that's all for this instalment of our new series! I apologize if I repeated myself at any point during this post, but the repetitive chapters covered sort of demanded it. Future chapters will have far less of this, I promise. Next week's, for instance, is going to be very focused on one specific topic, but it will also probably be more infuriating to you. Why? You'll see when we get there.

For now, have a good week and read something fun to wash the taste of this mess out of your mouth. Fandom might be dying, but you don't have to be. There is plenty to look forward to and far better things to indulge in.

With the growing field of NewPub, you can now do anything you want. Fandom is dead, as is the 20th century they were spawned from. Go out and do what you want to do.

The future is more than potholes and dead ends.

So much crap, so little time. 1st, not knowing (or caring) where your literary traditions come from is a recipe for screwing things up. Those traditions survive because they work. No, you didn't really just invent fire and the wheel.

ReplyDelete2nd, Mickey Spilane as a utopian writer? There are places in the novels when not even Mike Hammer wants to be in his world. That it's a bad place that requires him to do bad things is kind of the point.

3rd, it's funny that the author buys into the social conceit of Starship Troopers. Not even Heinlein would have supported such a system in real life, as we have real world examples of the power hungry joining the armed forces just for political legitimacy. It does track well though with the "Fans are slans" idea.

The very first scene of the first Mike Hammer book is him saying a prayer for his old friend while barely holding it together after learning what happened to him. That sets the tone for every story going forward. If someone thinks this is "Utopian" then they are clearly not paying attention.

DeleteI have a feeling the author of this book wasn't really paying attention.

This is good stuff; you draw a lot of insight out of this trash. I am impressed by your endurance.

ReplyDeleteWhat are the odds that, not only does a group of people who claim to discover the future get it consistently wrong, they also refuse to recognize the failure?

The odds are definitely pretty good.

DeleteThank you for reading!

Even the parts they get right are a product of self fulfilling prophecy. Elon Musk is on his way to being D. D. Harriman, but that doesn't mean Robert Heinlein was able to predict the future. It just means his work inspired a smart South African immigrant to be the guy from one of his stories.

DeleteEven better than Part 1, the which I was heading over to ask you a question about, and then ypu answered in this excellent book dissection.

ReplyDelete"This attitude is where that nonsense Arthur C. Clarke quote about Magic essentially being Science we don't understand came from. You have so little respect for people who came before that you think they are dimwits due to the age they were born in while you are a genius because of your birth year. Not only do you not even understand what Magic actually is (Hint: it has nothing to do with Science)"

ReplyDeleteSo magic is actually either a dangerous force or evil? just asking for a otherwise good response, Cowan

"The fantastic novel, in the form we know it, appeared first during the Age of Enlightenment, with political satirists like Voltaire (Micromegas) and Lud-vig Holberg (Nicolai Klimii Iter Subterraneum), at about the same time as authors like the Marquis de Sade explored the subconscious in works like One Hundred Days in Sodom and Matthew Gregory Lewis with The Monk."

ReplyDeleteI note the inclusion of the Marquis de Sade, and that his works are characterized as an "exploration" of the "subconscious." His work is more like an apologetic for the sexual sadism to which he has granted his name, based on a jejune philosophy that, since there is no God, all appetites and passions are equally valid, and must be fulfilled, including the most perverse. It is literally the philosophy of insanity. Voltaire, of course, is a notorious atheist, but does not venture as far along down the dark road, at least in print, to hell. I note also an absence of any other tales of the fantastic.

I note particularly the absence of Thomas More's UTOPIA, which satirized the arid yearning for the communism of Sparta that afflicts so many intellectuals of his day, and ours, and the absence of GULLIVER'S TRAVELS, whose wall-eyed Laputans and dispassionate Houyhnhnms are spiritual brethren to Mr. Lundwall.

For Mr. Lundwall, it seems the only the storytellers who mock and erode Western civilization, degrade faith, uphold filth, to be considered worthy ancestors to "science fiction," which, as you so trenchantly point out, Mr. Lundwall regards as merely a convenient tool of social engineering.