When things work correctly, you shouldn't notice them at all. This is a major part of what makes a stable society work. It also ends up being the downfall of said society when the next generation to be given the keys doesn't understand this truth. Part of the reason you notice so many things that are off these days is that just about everyone has forgotten what makes the world tick. Until we relearn it, we are doomed to a cycle of making the same dumb mistakes.

The arts are no different. In fact, you can learn how bad any society is by the entertainment they put out. A culture that lives off subversive remakes of old properties is one incapable of making anything new. One perusal of any overpriced streaming service should easily show you that much. It is a society that sees no future for itself so it must reshape the past endlessly.

All of that aside, one smaller part of the problem is that we've forgotten what pacing is. Not only have we forgotten it, for many younger folks it's never been a reality for them at all. Before we even begin to fix things that have gone wrong, we must understand what the present is doing so much worse than the past. In this case, I find it is pretty straightforward. Nonetheless, I will try to explain it a bit for the younger crowd who might not know.

If you've been engaged in entertainment for any length of time, you've noticed how horrendous pacing in storytelling has become. Unless you are younger than a Millennial you might not even know what good pacing even is. This is because you've grown up with an objectively inferior experience from older generations. It's not a nostalgia thing, it's a craft thing.

Of all the things to complain about in modern storytelling, I think this subject gets less talk than it deserves, possibly because it is difficult to quantify. But that is what is going to be done in today's post. We need to go over the pacing problem currently landing a wrecking ball into basic storytelling. there isn't a single genre or medium this issue hasn't done damage to.

So without further ado, we shall begin. Just what is the problem with pacing? It is in the action. Let us go into what that means.

The strangest aspect of entertainment today is how absolutely slow it has gotten. This isn't a new problem, but an old error that always returns during times of decadence and bloated egos seizing control of the arts. On Cannon Cruisers we constantly use the term "1970s pacing" to refer to movies with needless padding that take far too long for the ball to get rolling, and there is a reason for that. The 1970s is a period where a lot of storytelling went inward and out of its way to chase off as much audience as it could. It got selfish and greedy.

The issue at play is that filmmakers began to think their product was more important than their audience, and it shows in a lot of the needlessly long films from that time period. It's an issue of decadence and unearned arrogance on the creator's part.

There's no part of storycraft you can botch more than pacing to tell your audience that their time is not as important as yours. When you tell a story, you are communicating an idea to your audience. When you refuse to tell it in as concise a way as possible, you are neglecting the ones indulging in said art. No one needs your story, but your story needs an audience. It is you that should be respecting them, not expecting them to bow to your whims. This was a big part of why 1970s cinema is one of the hardest eras to go back to, outside of a handful of other examples such as b-movies. This is mostly because the B-movies respected the audience more than the "important" films from the time period did. There is a reason "important" '70s movies rarely make re-watch lists.

Cinema aside, I've been reading a lot from the 1970s/80s horror paperback wave this past year, ever since I went through Paperbacks From Hell, and I learned something I should have already known since I realized it in other mediums and in many other things I've read about and experienced in the industry. OldPub really did not respect the reader's time, just as they don't now.

I've been stuck on a certain book for a few weeks now, slowly going through it because the concept was initially really interesting to me, but after getting over 250 pages into a 400 page paperback I've come to realize that I've grown very impatient with OldPub books. I can see the formula holding these books back from being as good as they could be, and it has gotten under my skin. Just like all OldPub genre books, it has to fill a word count and be a certain length in order to be stocked on big chain store shelves, and I can feel the lack of editing and the over-usage of padding to get it to that pre-determined length. However the original story was meant to go I don't know, but I do know several top notch editors that would have put a redline through at least 60% of this book for being redundant, filler, or being stretched way too thin.

But here is the kicker, and the part that knocked my enthusiasm over into the waste basket. The story is supposed to be a horror tale about a drug that brings violent hallucinations upon its user, a very cool concept that could lead to a lot of horrifying or unsettling moments. Then reality hit me that I wasn't read a pulp story but a modern genre book. I should have known better. Not only did I not get that, I get everything I expected from a post-1980 genre book.

Instead, the central concept is used three times total in the first 75% of the book, and only one of those scenes last longer than a page or really affects the longer plot. The rest is a boring back and forth war with a single drug dealer and one crony, relationship drama between "broken" people, and needlessly following every step of another character in scenes that could have been summed up with a paragraph when he joins the plot later. Then there is the whole prologue which is the definition of "Short story as chapter" that was completely unnecessary for the audience.

It's not really a horror story, despite the advertisement that it was supposed to be one. There isn't really any horror here, it's just another modern thriller with a vague supernatural presence that, for the majority of the book, wouldn't matter if it was excised entirely from the plot. The thing that makes it unique is the thing that they barely touch on. It's maddening, and it reminds me of why I had a hard time reading when I was younger.

The concept failing aside, it is pointlessly sluggish. There is a clear disrespect for the reader's time, though I don't think that mistake was intended by the author. The editor is really to blame here, because it doesn't feel like they did much of anything to tighten up this story.

A lot of these faults may be due to the fact that it's the author's first book, but there is so much needless padding and waffling that you can be certain is the decision of an editor. It was clearly an editor who told the writer to add unnecessary fat and refused to cut redundant plot points that didn't need to be dwelled on. Instead of editing down, it was edited up. In other words, the book exists as it does in order to fill shelf on a bookstore, not because the story needs to be the way it is. You can blame this on the lumber side of OldPub's business model for why they champion horrendous pacing and have for around half a century, at this point.

It's a lot like in '70s cinema where the first 20 minutes of the story would be stretched to almost double the length, thereby making the movie interminable to sit through. For some unfathomable reason, in 1970s movies it is the first quarter and third quarter of the movie that tends to go on way past the point of tolerance, whereas the second quarter and finale are usually the same as every other era. It is as if they want to keep you from the action, the movement of the plot.

There is a reason I came up with the hard rule for action films after watching so many from this time. It's simple. Rarely does an action movie ever justify being shorter than 80 minutes or longer than 100, so ones that break this rule tend not to be very good on a fundamental level. Rushing through the story shows a lack of craft, and stalling shows a disrespect for the audience's time and overestimation of your own talents. An action and adventure story is meant to introduce quickly, then get to the rising action ASAP. The audience needs to be wowed as soon as you can do it, but do it too often or take too long to do it and they will rightfully drift off. Remember, they are here for the action. they aren't here for you to waste their time.

This means knowing when to end the story. Action stories should be as short as possible because the audience will get burned out or even desensitized to what you do. The faster and stronger your punches, the quicker the fight is won. Are you in a fight with your audience? In a sense. You are fighting to keep them engaged, and they are engaged in action and adventure because they want to see action and adventure. The less they get of it, the less they will want to stick around. You need to offer it to them while also making sure they stick around for the whole ride. This requires respecting their time and knowing the right way to cater to their needs.

Think of it in movie terms, such as the above. Imagine the shortest limit I put up there, an 80 minute action movie. How would that work? How do you make a movie so short and yet mange to hit all the right points? Naturally, few movies are as short as 80 minutes, but it appears to be the bare minimum you can go before you start losing things you need to make the story work. In essence, an 80 minute action movie would be the bare minimum required.

I will describe it in four blocks.

First 20 minutes: Introduction

In the first 20 minutes, you need to introduce your protagonist, their goals and why we should root for them. you must do the same for the antagonist. At the same time, the conflict between the two, why they are opposed, is to be set up. where most action movies go wrong as bloating this up with big, elaborate back stories or convoluted motivations in an attempt to be clever. You don't need to be clever, you need to be clear. Tell the audience straight out what they want to know. The longer you take to set it up, the more you risk the audience tuning out.

At the same time as the above, you need to have some action early in the story to give an indication as to what the audience will be expecting for the rest of the movie. This chunk of time is essentially the entirety of the first act, and it's very necessary. It's important set up, but dragging it out too long risks boring the audience and blowing through it too quickly risks confusing them. I can say, audiences will be looking at the time if you blow past half an hour on setup, and that is the last thing any moviemaker should ever want.

Second 20 minutes: Rising Action

Next, you ratchet up the action, leading up to the second act turn. Whether the heroes or villains suffer a win or loss doesn't matter so much as that the actual situation changes by the end of this conflict stage. The status quo must be rocked, and it must be reflected in the action. The carnage here must trump everything that came before, otherwise the audience will not feel the tension as best they need to stick with the story. Remember, this is action!

When this part ends, it shouldn't contain finality, but just enough of a shakeup that means the protagonist and antagonist have unfinished business and, to use an old cliché, that said business is now personal. If it isn't personal by this point then the characters are not as invested as they should be, and neither will the audience be.

Third 20 minutes: Tension Release

Yes, action stories shouldn't have constant explosions and knife fights. The audience needs to take in what just happened and learned how it affected what the characters have just gone through. Just as the introduction builds to the chaos the audience just experienced, so to must it be built again. This is the one period of the movie where there should be a lull in the action, the audience needs a breather and requires catching up with what just happened.

At the same time, the plot needs to continue towards the setup for the final confrontation. Linger too long on downtime and you risk the audience losing interest again. You need to remember that this is an action story, so things still have to move. All the pieces on the board must come to the place they need to be for the final checkmate. The hero says goodbye, he might not make it back, etc. Get ready for the climax, because this is all going to explode.

Fourth 20 minutes: Climax

This is where everything goes off the rails, in a good way. Everything has led to this moment, and the action needs to reflect all the buildup you have had so far. But it isn't just a final release. Even during the climax does the action rise, leading to the iconic standoff between protagonist and antagonist, where it is released in a battle of wills that can go however your story is meant to go . . . but it must top everything seen so far. It leads to the final moment when both hero and villain exchange their final (possibly metaphoric) blows with each other, and the correct party walks away. Do this right and the audience will be pumping their fist as the cheesy rock song plays and the credits roll over the remaining debris of what was just unleashed.

You'll notice I didn't put "denouement" in its own category. This is because action movies shouldn't have them. The story should end as close to the villain's defeat as possible, letting the audience leave on the high they came in for. The longer you risk going on and on after the final confrontation, the more you risk losing the effect you worked so hard for. You want the audience feeling like something got accomplished, and it meant something. That final image is going to stick with them long after they've put that movie back in the case again. This is what any creator wants the audience to feel.

This is the key to making a good action movie. It requires an order to the chaos, just as most storytelling does. It prioritizes giving the audience what they want through tight pacing and parsing out gold nuggets of action in all the right places. Every classic action movie does this.

Yes, the above formula does look a lot like the Lester Dent formula, but since it we are working with visuals and not words there is a lot more to keep track of. Director-style, actors, execution of action, and even cinematography, can change the amount of time it takes for any of these things to happen. However, if you risk going over 30 minutes in any of these categories, you risk losing the audience entirely. Hence why there are few good action movies that break the 2 hour mark, and none that reach 3 hours without severe pacing problems. These movies simply don't warrant being that long because they go against the point of action, which is to be quick and brutal.

And sure enough, as long as I've been doing Cannon Cruisers and have covered well over 100 movies by now, this unwritten rule appears to have been put to good use. Just like most stories, there is a clear winning formula at play here.

Next time you watch an action movie, try to keep it that above formula in your head. You'll notice each part falls somewhere within the 20-30 minute limit I've described. For good reason. Most classic action directors knew how to put audience needs first.

But this is just one medium.

In a prose story, you have a lot more room when it comes to overall length. You have different forms such as short story or novel to work with. Even with novels, you aren't limited to a length. A movie has to be a set length in order to work for the single-sitting experience it is required to be, but a novel has many options for its many different sizes.

It has the options, but OldPub doesn't use them. While action movies were exploding in the 1980s, action books were dying. And now they no longer exist in that system. Instead, everything has been codified into one bland mashup thriller genre where everything is the same length with the same covers and with the same plots. It has no fangs.

OldPub has done nothing but fumble the ball in this aspect. By pushing everything into one neat little 400 page package, it has stifled the potential of many modern books into falling to a mushy baby food formula. This is exactly why I can't read them as easily as I can older books. A long time ago you could find anything on a shelf and it would be wildly different from the thing next to it. Now you walk into a modern book store and see a sanitized shelf of the same safe paperbacks operating under the same tired clichés and you already know everything you're going to get. And it is not going to feel as satisfying as a story that flows freely.

For example, Lord of the Rings justifies its length by offering enough of a story that it can support being large--people aren't coming to Tolkien for pistol duels or fist fights. They are coming for a wide open adventure that will wow them. He wasn't setting out to write "Epic Fantasy" in the OldPub checkbox mold; he was setting out to write the story that needed to be written. Hence why the story, despite being so long, is expertly paced.

However, this isn't how it works in OldPub; you are meant to work for the wood pulp printers, not the audience. This means your editor is going to make your story bend and break to get on that shelf at the correct length to fulfil quota. This leads to you promising an exciting story on the cover and instead delivering an uneven and flaccid experience with occasional spikes of violence or death, full of subplots that do little but stall forward momentum. This is how you get a modern OldPub book.

This is how you get the book I was referring to above. The audience is left with an experience that isn't as good as it could and should be.

What I am saying is that the above book squandered its potential by having to fall into the incorrect formula, because OldPub is as bad at setting up formulas as it is at selling books. But this wasn't even the first book I've even talked about on this blog with similar issues. In fact, I know there is far more I haven't touched that contain these issues, and more.

Several horror novels from this time period suffer from pacing issues. Ghost Train should have had a hard edit to bring down its overlong length, and The Keep, awfulness of the story aside, was interminable with constant repetition. These are books that would not have been harmed by losing at least 100 pages of their length. Most of my experience with paperbacks from post-1980 fall into this camp of potential being squandered by editors not directing writers in the correct direction. We know why they didn't, but it is still maddening to see happen.

However, in my reviews of both Nightblood (a longer book) and The Spirit (a short one) I came to the opposite conclusion of the above two. Nightblood entirely justified its longer length by having enough story to tell and masterfully employing escalation as it goes along. It's a story that is the exact length it needs to be The Spirit was pulp length and was perfect for it, knowing exactly the right time to bow out without wasting a single word. It needed to be short to have the power it has. But neither of these were the typical length of modern paperbacks, breaking with apparent tradition of the era. Instead, they were merely allowed to be what they were supposed to be.

This is how it should be. A shelf where every book is the same length would look, not only bad, but wrong. Perfect pacing means knowing the right size a story needs to be, which means they are not all going to be the same size. That's just obvious. Speaking as a writer, if every one of my books came out looking the same I would think there's something off with my storytelling ability. No two stories are the exact same length, unless they are artificially tweaked to be that way.

So you can see why it is disconcerting looking at the shelf of a modern OldPub bookstore chain. It is clearly not how it is supposed to be.

And that was one of the things that turned me off of going into the big book chain stores, when they were still around. I would look at the uniform covers, the uniform length, and the clearly carefully researched uniform blurbs, and feel like I'm walking into a book factory, not a store selling stories. It felt far too fake.

Writing formulas are flexible, but no less reliant on pacing to tell their story. Movies need to fall into a sweet spot, a pocket, in order to reach their true potential. So do TV shows, comics, and even video games. Books, however, do not. They can be anything, which is their greatest advantage. And yet it feels as if writing today has the tightest straitjacket of them all.

This is one of the reasons the pulp formula has taken off so well among NewPub authors, because it works for every story of every length. Get the pacing down, and you can do whatever you want. This is how it should be.

If after 250 pages in a 400 page book, you've barely touched on what is supposedly the selling point of your story, then you have made a critical error somewhere along the line. It's a good bet that someone expecting a horror book about a drug that brings hallucinations to life shouldn't have to see it a grand total of three times 75% of the way through the story, and only one of the three really affecting much in the way of plot. I didn't pick this book up to read a generic modern thriller with a typical modern romance subplot that moves along at a glacier pace. But there was a formula to fit in order to cut paper costs, so the story has to suffer for it. you're not buying an OldPub book for the story, you're buying extra stock from a wood pulp paper company.

And it shows.

As a result, I'm not going to review the book in question which is why I haven't mentioned the title thus far. It's obscure enough that you probably won't find it unless you're deliberately looking for it anyway. However, I'm also not sure if my problems come from the author, first book issues, or simply that the editor had their priorities all wrong. Possibly a combination of all three.

Either way, it seems fairly clear that OldPub hasn't had a story-first mentality since at least the 1970s, if not far earlier. By the 1980s, they were already falling behind the success of movies due to this practice. It's no wonder that no one reads anymore. You couldn't make a potentially exciting industry less exciting if you tried. This is the where OldPub has led us. So you can see why I don't spare time heaping praise on them.

Every bookshelf stacked with their product looks exactly the same. No wonder I would get bored so quickly at every chain bookstore I went into. It's all so stale and utterly predictable. Every one of them looks like this:

Thankfully, that era is coming to a close. With the NewPub revolution, you can write whatever you want and even find an audience doing it. Just be sure to get a good editor and cover behind you and you're all set. You don't need this industry anymore.

I would argue that pacing is more important to writing than ideas are. You can get ideas everywhere from dreams to having a random thought while watching a leaf fall from a tree. You can only get good pacing with practice and an editor that cares enough to recognize its importance. A good idea can be enhanced by good pacing. Good pacing can't be dragged down by a bad idea. Their are copious amounts of movies with bad writing that are still beloved which prove that true. The audience will forgive just about anything if they think you respect them.

I'm not going to tell you to pay closer attention to the pacing and obvious formula the next time you read an OldPub book, if you even do anymore, because I don't think it's necessary. You know deep down when something isn't quite right, and everyone is fairly aware that something isn't right with the OldPub system. Instead, I'll just tell you to read NewPub instead. You can find much better outside of the wood pulp stores.

Readers are ready for a return to action, and I intend to give it to them, as do other in the new world of publishing. Come join us as we take a steamroller over the old ways and build a new future worth looking forward to. It's going to be great.

Be certain, we won't waste your time.

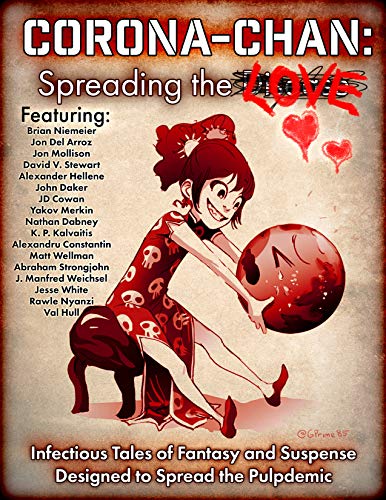

For a FREE collection of NewPub stories, check out the bestselling Corona-Chan Anthology! Stories of action, adventure, comedy, and wonder. It's been a whole year since we first put this out, so be sure to give it a download!

This is one of my problems with Anne McCaffery books. For instance, the Crystal Singer. We're promised a world where Singers sing crystal while fighting to awaken from blissful trances in time to escape the storms that sweep the crystal mountains and turn the whole planet into a harmonic death trap. What did we get? The heroine sings crystal one time. The rest of the book is garglemesh about who is sleeping with who. It's slow and boring. The climax is unexciting. I've never been so disappointed in my life. The Dragonriders books are the same way. They're sooooo awfully boring. I'm thankful for modern NewPub authors like Marc Secchia who take the dragonrider idea to the most amazing, fantastic, fast-paced heights, with clever writing and characters who pop. Such a far cry from the old "classics".

ReplyDeleteThat sounds exactly like the problem with old publishing. Cool ideas are neat, but if you don't use them then what's the point?

DeleteYou've hit the nail on the head, JD. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteI also noticed this when going back to read Vernor Vinge's otherwise-excellent A Fire Upon the Deep. When I first read it, I loved it for the vibrant worldbuilding and mind-blowing ideas.

But upon re-reading it a couple decades later, after having drunk deeply of older, better-paced pulps, the story is glacially paced and feels padded-to-order by an editor probably keen to hit a certain page count to get the doorstop profile that was en vogue at that point in the TradPub SFF business.

How much do you think this all has to do with the economics of paper, and how much with genre fiction trying to ape the superficial forms of Classic Literature in order to be taken more Seriously? Plenty of 19th century literature has survived in spite of terrible pacing. (I'm looking at *you*, Tolstoy.)

I think it might by both. OldPub encourages this because it's more cost efficient for them to push doorstoppers. It explains why so many modern books are the exact same length. There are also a lot of authors who are taught to write "important" books and end up overindulging themselves.

DeleteThe more I read old books and the more I write, the harder it is for me to look past obvious pacing issues that simply shouldn't be there. Maybe it's a bit like knowing how the sausage is made, but it is harder for me to put aside than it used to me.

the most controversial writer advice I've seen that manages to get a lot of authors mad is that "your story should be as short as possible" which is simply truth. It gets interpreted as looking down on longer stories when it is the opposite.

Every story has a specific length it needs to be. When you artificially lengthen or shorten it, readers can tell. They might not know the finer points of how it's done, but they can feel it in their gut.

The best solution is to just let things be what they are. Everyone wins that way.