Over the last few days, I've been witness to some discussions that solidified a few thoughts I've had floating at the back of my head. At Wasteland & Sky we discuss art a lot, because it is both more important and less important than some believe. It is more important because it shares ephemeral ideas and notions we all need to experience over and over, it is less important because it is not a god for a cult to worship. Art is connection, not the end goal. Recent discussions have made this clearer than before.

That recent series of events have proven to me that investment matters more to the audience than any other area of craft. While craft matters a lot (you can't create art without it) it is secondary to the end goal. As stated before, it is connection. Audience investment is what will truly make the difference between good art and memorable art.

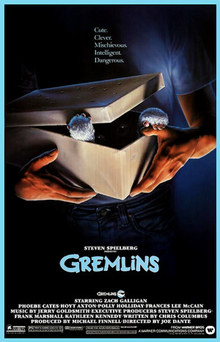

After looking over author Brian Niemeier's review of the two

Gremlins movies, I thought about one thing he mentioned in regards to the first.

It was the following:

"On the flip side, sometimes flicks that shouldn't work by any accepted metric defy the conventional wisdom and strike a chord with people. I recently re-watched Gremlins, and it struck me as a perfect example of David Stewart's IP explosion phase. Shot on a shoestring budget from B movie material not even the director believed in, it became the fourth biggest film of 1984.

"What's even more amazing is that according to the rules, there's no way Gremlins should have been a hit. The film makers somehow managed to cram nearly every screenwriting mistake in the book into the first act. The magic system is infamously illogical and arbitrary. It takes forever for the first gremlin in a movie called Gremlins to show up. Entire subplots and characters are introduced, only to be forgotten by act two. It takes until act three for a clear protagonist with a concrete goal to emerge. Same goes for the main antagonist. The horror often clashes; not just with the comedy, but with other kinds of horror.

"And despite all those demerits that would have turned a lesser movie into cringeworthy schlock fest, Gremlins quickly achieves an intoxicating level of fun that it maintains all the way to the end."

How did it manage to achieve classic status despite all its objective faults? We will get to that, but this is not the only recent discussion that spurned the creation of this post.

Another discussion was one on social media wherein a fanfic writer (of some notorious NSFW pornography) went on about "Rules for Writing" that included "rules" that were nothing but the writer turning their pop cult orthodoxy into dogma. This is the opposite side of "investment" where the consumer of art turns it into an idol.

Their "rules" included such gems as characters not being redeemable if they've killed more than 10,000 people (999 is okay), how the sitcom Friends is a good example of writing to be emulated, and how writers need to keep away from "bigoted story decisions" if they want to succeed. Those are just three points in a 100 point thread that has since been deleted due to being quickly turned into a punching bag. However, it was quite funny to look over as a writer and see the supposed advice get progressively crazier, more obsessive, and incorrect as it went.

Just for clarity's sake, before we continue let us talk about why those three points are wrong and written by someone who doesn't understand storytelling. It will roll into the topic later on, so please bear with me. Pop cultists know what they obsess over: they do not understand why normal people like the things they do. This list proves why you should never cater to fanatics. They are always fanatical about the exact wrong thing, and sometimes it's a thing that doesn't even exist.

But I digress. Here are three things that a pop cultist believes is the key to success. This is what they believe will invest others in stories.

- 1) Characters who kill over 10,000 people are irredeemable

First of all, redemption doesn't work that way. There is not a finite number of horrible things you are allowed to do before you can no longer turn back from the dark. Only someone who doesn't understand forgiveness could think this. Ironically enough, the same people who believe in permanent evil also tend to think anyone can turn evil at the drop of a hat, even if they spent their entire life being white hats. You can just smell the despair.

Audiences will accept both a tragedy or a redemption, no matter what either character does, if it's written well. People who engage in art on healthy terms know what they want from a story on a deeper level, and pop cultists do not because they are disordered in their thinking. A story of redemption or a tragedy are two styles that have lasted since storytelling began, because they are ingrained in us as things that can, and do, happen all the time. You know this if you have a healthy outlook to understand human beings from.

There is nothing more frightening than falling down a pit of despair and destroying everything you've built up by making a simple series of bad decisions, and there's nothing more hopeful than a sinner who has nothing then bowing his head and asking for a second chance to turn it all around. A storyteller knows this just as inherently as their audience, which is why it is as common as it is. It works.

In other words, this point is exactly wrong. A writer that doesn't understand the concept of redemption is not a writer. He is a defeatist putting his own warped worldview into his work. And as we all know, cultists can't help but be warped.

- 2) Friends is an example of good writing

In case you are unaware, because no one under the age of 25 will, Friends was a sitcom from the late '90s. It was about a group of six urbanites living in the city and dealing with superficial life problems while having sex with each other and dealing with plots about nothing. They did not go on adventures, they did not do anything worth noting, and they were completely selfish and self-absorbed. It was essentially Seinfeld, except completely unaware that these were bad things, and vapid as a result. You haven't heard about it since it ended because it had absolutely no staying power.

It only came to popularity because Seinfeld ended, before then it was just another Young Adult sitcom from the era that was obsessed with modernity and perversion. Friends received its explosion in popularity due to being a pale imitation of Seinfeld that leaned on soap opera plotting and '90s fads, none of which have aged well, and none of which has any relevance to normal, healthy people. The best '90s sitcoms still get talked about to this day, Home Improvement, Boy Meets World, Frasier, etc., but Friends does not get mentioned except as a nostalgic footnote. Everything it did was done better in countless other places, and it has no remaining appeal for those who didn't watch it when it was first on.

As you can tell, this doesn't make for the best example to model anything after. The last thing you want to do is date your work with what is flashy and current, because chances are that once the honeymoon ends no one will remember it as anything for the empty calories it was.

On the other hand: Friends was also a sitcom. It is not an action story. If you're not writing a sitcom for television, then you should not be writing a sitcom in your space adventure or period romance story. They are very different styles of stories meant for very different audiences. If your audience wanted a sitcom, they would go watch a sitcom. They are coming to you for something else. If you're reading stories for shallow soap opera drama the there are plenty of other places to get it.

Audiences are invested in you for a different reason than when they pop in a season of Married With Children into their DVD player. Give them what they want. It's really that simple.

- 3) "Bigoted story decisions" will harm your story

This is a big one you see a lot from writer workshops, and proof that OldPub has no idea what they are talking about. This is a way to make sure you don't tell stories they don't like, but it is wrapped up in nonsense jargon to obscure the real intent.

"Bigoted" writing means nothing, but it is a way to control what you write. You are simply not allowed to have certain story turns because it might offend someone of some group somewhere, and that's just bad. Therefore you must write by the right rules, which just so happen to be the ones OldPub and Hollywood, both currently failing, want you to do. You need to write stories that check the right boxes to make sure you don't hurt some group that may or may not exist. If you don't? Well, that's what cancel culture is for.

Isn't that just convenient?

Here's the secret: there s no such thing as a "Bigoted story decision" because a story decision can't be bigoted. That's not how writing works. That's how hacks work.

This one is going to need some explaining, so bear with me.

Whether you are a plotter or a pantser doesn't really matter here. When a writer comes up with a story and when they write and down and edit it, they are attempting to clarify a story that has sprouted in their mind. It is their job to clear it up for consumption, sort of like a window washer. They are attempting to clean and polish that picture clear and present it to the reader. The writer is a glorified delivery boy to their stories. That is what creativity is. Nothing is invented by whole-cloth.

The only reason you might disagree with this is would be if you have elevated writers and creators to the level of high priests who exist to deliver dogma to the unwashed masses. This is what a pop cultist believes, not what a healthy human being believes.

So when you read an old pulp story and they have salty language, or say mean things you don't understand, it isn't because the author views the world the same way as his characters, it is because the character sees the world that way. The writer is writing the story forming in his mind. If the narration is using terms you find offensive it is because that is how people talked at the time. Writers aren't able to use their psychic vision to see what will be considered acceptable by you half a century after they have died. Believe it or not, most people in history did not act and think like an over-socialized urbanite who thinks everyone who votes differently than them is literally Hitler or stupider than someone who pays the majority of their paycheck to live in a rat-hole of a city apartment. Most people are actually normal.

You can be arrogant about it and consider the world as having "advanced" since the old days, but then you are being oblivious to the fact that your work will be considered "bigoted" one day too, and maybe not even for good reasons. This is the problem with constant purity tests: it misses that the point of art is to communicate. The past cannot adapt its message to suit your fragile ego: it is what it is. It s up to you to adapt to their mindset and understand what they were trying to communicate beyond your shallow worldview.

There is no such thing as an "unbigoted" story, because writers don't write to proselytize messages. They write to connect their story to the audience. Checkbox writing is the writing of cowards with nothing to say or communicate but think they should be listened to. You cannot write stories that way. Your audience doesn't exist for you to sermonize towards them.

Your audience has a relationship with you. They will never be invested in what you have to say if you are more worried about caving to popular demand than you are delivering them what they want. See modern Hollywood and OldPub for hundreds of examples of just this failure.

It is OldPub because it is old and decaying. Taking examples from them is like taking humanitarian lessons from Ira Einhorn. It's a fruitless endeavor.

What those three points were meant to do is make you think a particular way when writing. It was meant to make you believe that there are things you can never do when being creative. These hacks mainly make these sorts of demands because they want all art to conform to their fetishistic standards of being a pop cultist. However, it is also because they don't understand the point of art to begin with. They can't, because they worship it as an idol.

As mentioned many times, art is meant to connect. This means one of your biggest tasks as a writer is to get your audience invested in what you do. To do that you need to connect to normal people, not fanatics. Fanatics will only ever be invested in what piece of art they fetishize, they are incapable of seeing the bigger picture. Normal people are capable of seeing everything, even if they don't always understand what made it connect to them.

So let us bring it back around to the original subject again. Why did Gremlins succeed at the box office and become a sensation despite having so many objective faults? Isn't there a formula for writing you need to follow in order to be good? If so, how did Gremlins surpass all of those to hit so big? Does this mean we should throw out all storytelling rules?

No, because Joe Dante did everything right despite not doing it perfectly, and what he did perfectly is what made the film a classic.

But how did he do it? As I commented on

Brian's blog, it was because Joe Dante knew what the audience wanted and delivered it above everything else. Because he accomplished that task the faults of the movie no longer even matter in the grand scheme of things.

For context, I re-watched the movie with a more critical eye for

Cannon Cruisers despite having seen it many times over the years. Because I had seen it so many times I thought I knew the film well. However, I soon noticed many things I didn't notice before when I wasn't watching it more intently. Characters disappear from the story, there are plotlines that go nowhere, and the movie just sort of ends without telling us the aftermath of any of the carnage. As a narrative, these are real problems that hurt the movie. Objectively, they are bad moves.

But no one really ever sees them. I never noticed these flaws until I paid attention to the film on a deeper level. The fact of the matter is that I didn't see these problems when I first saw them, and most others didn't either. Many people still list Gremlins as one of their favorite movies, despite its objective issues. The faults simply don't matter.

So how does that work? Why are audiences able to overlook the problems? What did director Joe Dante do to warrant such acclaim and popularity for a movie even he knew had flaws?

The answer is surprisingly simple: he gave the audience what they wanted on a deeper level. All the important things audiences crave are embedded in the final product. He gave them what they wanted, by giving them what they needed.

There are four points every story needs in order to engage the audience. They are easier said than done, but every classic story gets these points right on some level. Gremlins hits all four of these handily and expertly.

- Characters that are likable

- Themes that resonate

- Action that flows

- Story that is coherent

I would say these are fairly straightforward, but let us go through each to see how Gremlins manages all four of these points. I would recommend seeing the movie first if you haven't, it is well loved for a reason. But either way, there might be some spoilers. You have been warned.

We should start with the first point. What is "likable" characters referring to?

The audience needs a character, it has to be at least one, that they want to see succeed and win. Stories are about characters getting from one place to another so the audience needs a reason to want to see that happen. Many experts claim you need to make your characters "relatable" for this to work, but that is completely backwards. Art is connection on a base level--no matter what story you write, no matter how alien the cast is, the one partaking in the art will find at least one of your creations they can forge a bond with, even those they have nothing in common with on a superficial level. They know what they want out of stories. You can't really write an "unrelatable" protagonist unless you deliberately want to. See recent Hollywood movies for examples of an embarrassing failure to this point.

Gremlins aces this with Joe Dante's respect for his small town. Billy, our main character, is a good guy who has a thankless job, has a quirky but well-meaning family, and all sorts of weird neighbors he has a connection with. Because of that, we also forge a bond with them. The fact of the matter is that we like every character because they have positive connections with each other and attempt to support each other through the story. It's very much the community we wish we had (or used to have, depending on your age or location) which in turn connects you to the town. Dante spends the entire first act making you invested in this place.

Then there's the mascot of the franchise, Gizmo. Gizmo is a cute little mogwai with a friendly attitude who just enjoys being around Billy. He's a pleasant character where most such mascots from the time are just annoying and in your face. By nailing what so many others fail with, Dante sets up Gizmo to lead a cast we like on a base level. So when the horror begins we have total investment in all the characters and what happens next.

This rolls over into the themes. Gremlins doesn't have much in the way of theme, it's meant to be a popcorn horror movie, but it does stress the theme of community and following the rules. When the gremlins attack later to "sabotage" (as they do) the lives of the townsfolk, they usually do it through their lesser habits and quirks. They are in essence, "sabotaging" the community through their own weak-points. The scenes of them running rampant and pretending to be people, while mocking them, shows how little respect they have for humans and society in general.

One of the faults of the film, and something a film like Critters 2 actually got right, is that it doesn't feature the town coming together to beat them at the end. Instead, they basically disappear. As said before, one of the faults of the film is that all the subplots and most of the cast vanishes in the last leg of the movie. But we still want to see Billy win because we like the town and those in it. We still are invested in ending the chaos.

The gremlins' weaknesses also work on a deeper level. Water doesn't kill them, but makes them multiply. This is because Gizmo, the original mogwai, is pure. It can be said that the water is a purifying agent that cleans him of his bad side and separates them into whole other beings. It does the same to actual gremlins, but because they are already evil, it doesn't purify so much as make them lesser, sort of like the movie Multiplicity does with clones of clones. This is why the final or boss gremlin is always the first one that springs from Gizmo. Food after midnight makes mogwai change into gremlins because their inner gluttony takes hold, which reveals their darker vices and shows what they truly are. Sunlight kills them for the same reason it kills vampires: they cannot face the pure light of the world they rejected. They epitomize the night life, society's lesser half.

While none of this is ever explicitly said, the audience knows all of this due to how it is executed visually. You know this without being told it. Joe Dante's direction is what makes this work.

The flow of action is also due to Dante's deft touch. Scenes are paced perfectly, getting across exactly what they need to and lingering enough that we get the gist. By this point in his career, he had mastered the director's chair.

The horror comes and goes exactly when it needs to, punctuating the tension and constantly raising stakes. This is actually why few people care about the faults of Gremlins: you don't notice them because of how expertly paced it all is. Audiences will forgive anything if you give them what they want on a deeper level, and that's precisely what Gremlins succeeds best at doing.

Even with the objective faults the movie has, one thing Dante still manages to let shine through is the story, despite its warts. Everything that occurs, every wild moment and strange reveal, is perfectly coherent and understandable. Unlike the modern error of assuming something is good because it confuses the audience, Gremlins is tightly paced to the point where every beat works towards the story. Even with the holes in the plot, the main thrust of the narrative, and the themes, are still in tact, and the story still makes perfect sense. You are never confused at any point while watching Gremlins, nor are you distracted from what story the director is directing you towards.

As opposed to the modern trend of having horror movies drag on an hour too long and teach obvious messages on a surface level that the audience already knows, Gremlins does the opposite. Its themes actually aren't overt and it also runs under two hours, getting in and out like an action, adventure, or horror story should. This is why it has achieved classic status and why none of the vapid clunkers that fanatics prop up today will ever reach that level. One attempts to connect with the audience, the other desperately wants them to understand what is sluggishly being put across because it has nothing else under the hood aside from its main gimmick.

If the theme is the entire point of the story then it is not a story: it is a lecture. It is only one part of a missing whole. You need everything above to create a story.

|

The movie in question

|

In other words, Gremlins is a classic because it does everything it needs to in order to connect with the audience. The objective faults are there, and they do matter, but they simply do not subtract from what makes it succeed with normal viewers. What it needs to get right it gets right in spades.

Unfortunately, it does have one blemish on its legacy that has harmed future films, and that is that it created the PG-13 rating, the rating that would eventually kill its genre and neighboring ones by allowing studios to create focus group tested product and sand off the edges to their stories to appeal to audiences that didn't exist. You can see the full fruit of this in the sanitized fluff that was the 1990s not long after Gremlins 2's release. We can't really blame Gremlins for doing this, but Spielberg insisted on creating the label after complaints of violence in the movie. If anything, he should accept the blame for preventing movies like this from being made anymore.

But we're getting off topic. The point is that Gremlins' success is entirely owed to the fact that it prioritized audience investment over everything else. It prioritized the right things over everything else.

This is, at its core, what storytelling, and art, is about. This is why audience investment is key in creating a good story, and why current Hollywood and OldPub cannot do it any more. They are not trying to connect, they are trying to force the audience into accepting unbelievable frames and checkbox characters that are not based on any rational form of reality. They expect you to puzzle out their non-human nonsense, and give them lots of money while doing it. Oh, and shutting up when you don't like it. Can't forget that.

What this ends up churning out is inhuman stories that feel like aliens from another galaxy wrote them. They just hire human actors to say their nonsensical catchphrases and hammy overacting poses while they go through the motions of presenting a story they don't really understand, because they don't understand who they are trying to reach. Even the worst B movies have more humanity than a modern Hollywood film. Because, at the heart of it, their main goal was attempting to connect with the audience: not expecting the audience to put aside their humanity to connect with them. Art is not a one way street.

This is why the rise of alternate industries such as NewPub is so important. People need art to give them hope and entertain them through darker times. They need art to stir imagination and reinforce their lives. The old industry has no interest in doing this anymore, they are too bloated and self-important for that. But the new wave of artists coming up will give you exactly what you are craving. There are new ones springing up every day.

Investment matters, because the audience matters. Creators should all accept this. Art is connection, and it will always find a way.

We just need to be willing to make the effort to bridge that gap.